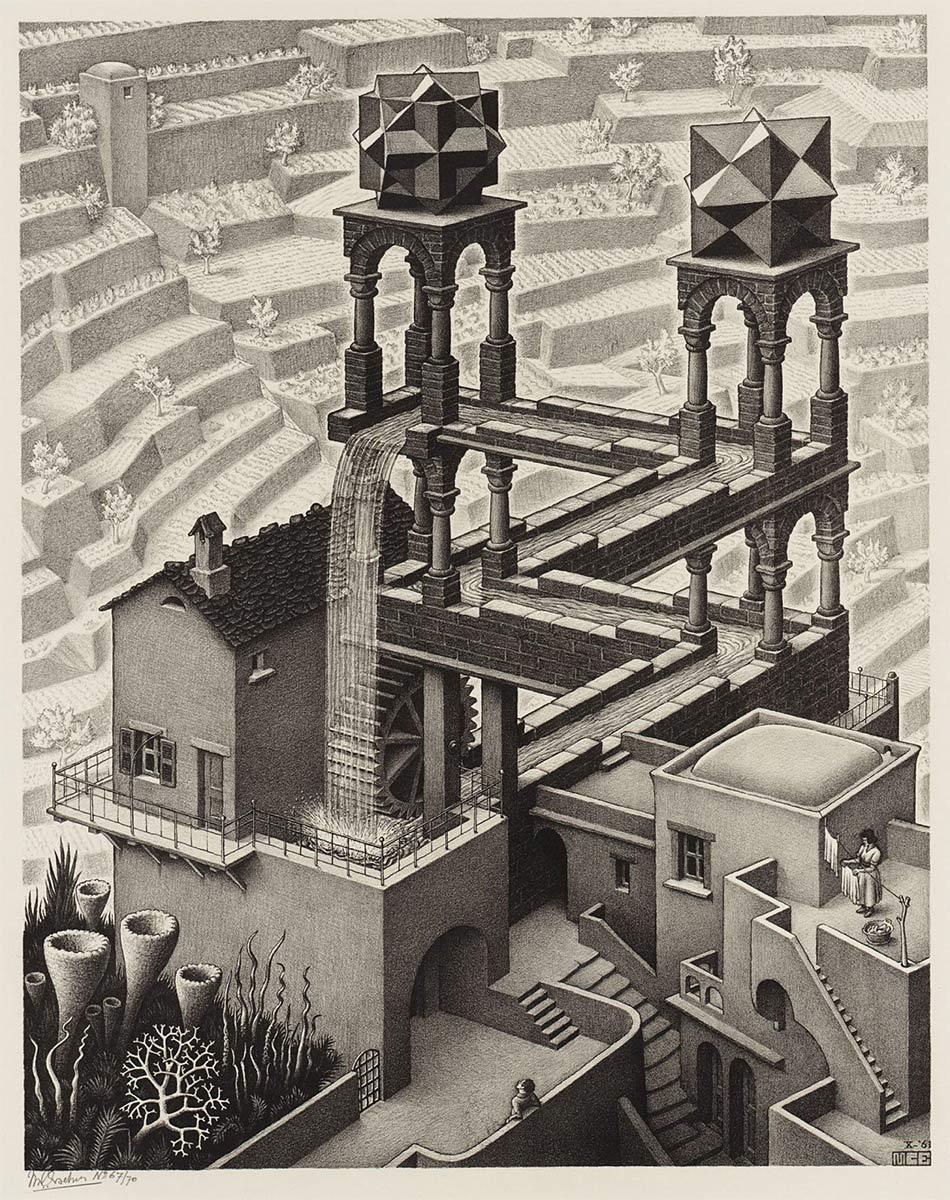

‘The fascinating OMG moment.’ This is how, in an edition of VPRO radio show OVT (see below, Dutch only), former curator Micky Piller describes the moment in which a viewer takes a second look at Escher’s lithograph Waterfall. At first glance, we see water cascading down from a raised platform. It looks straightforward enough. But on closer inspection the viewer experiences the OMG moment, when the brain cannot make sense of what the eyes are telling it. The water is flowing upwards. Upwards?! Waterfall is the work in which Escher deceives his viewers in the most direct way.

Escher created a number of world-famous prints that you could safely call iconic. Consider in this regard Day and Night (1938), Metamorphosis II (1939-1940) and Metamorphosis III (1967-1968), Reptiles (1943), Drawing Hands (1948), Relativity (1953), Belvedere (1958) and Ascending and Descending (1960). But this lithograph from October 1961 is perhaps the most famous of them all. Probably because it is this print that hits you the most after an initial look. It affects all kinds of people in this way, from young to old and from seasoned art lovers to less experienced viewers.

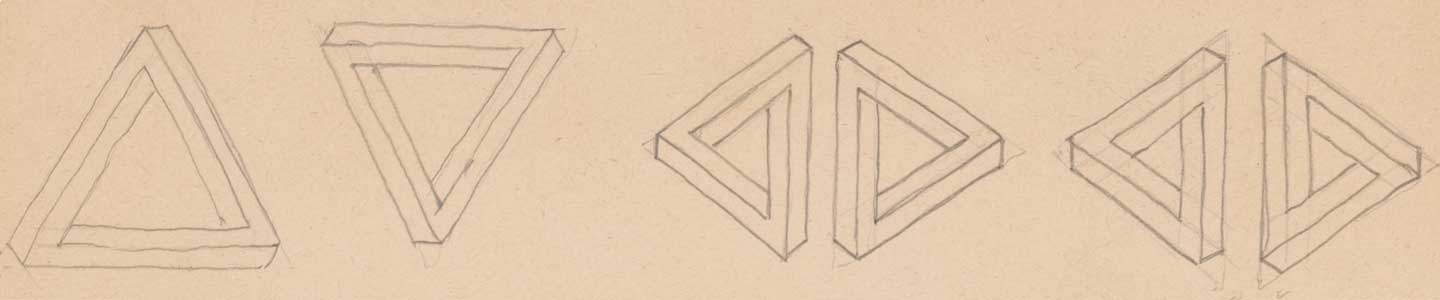

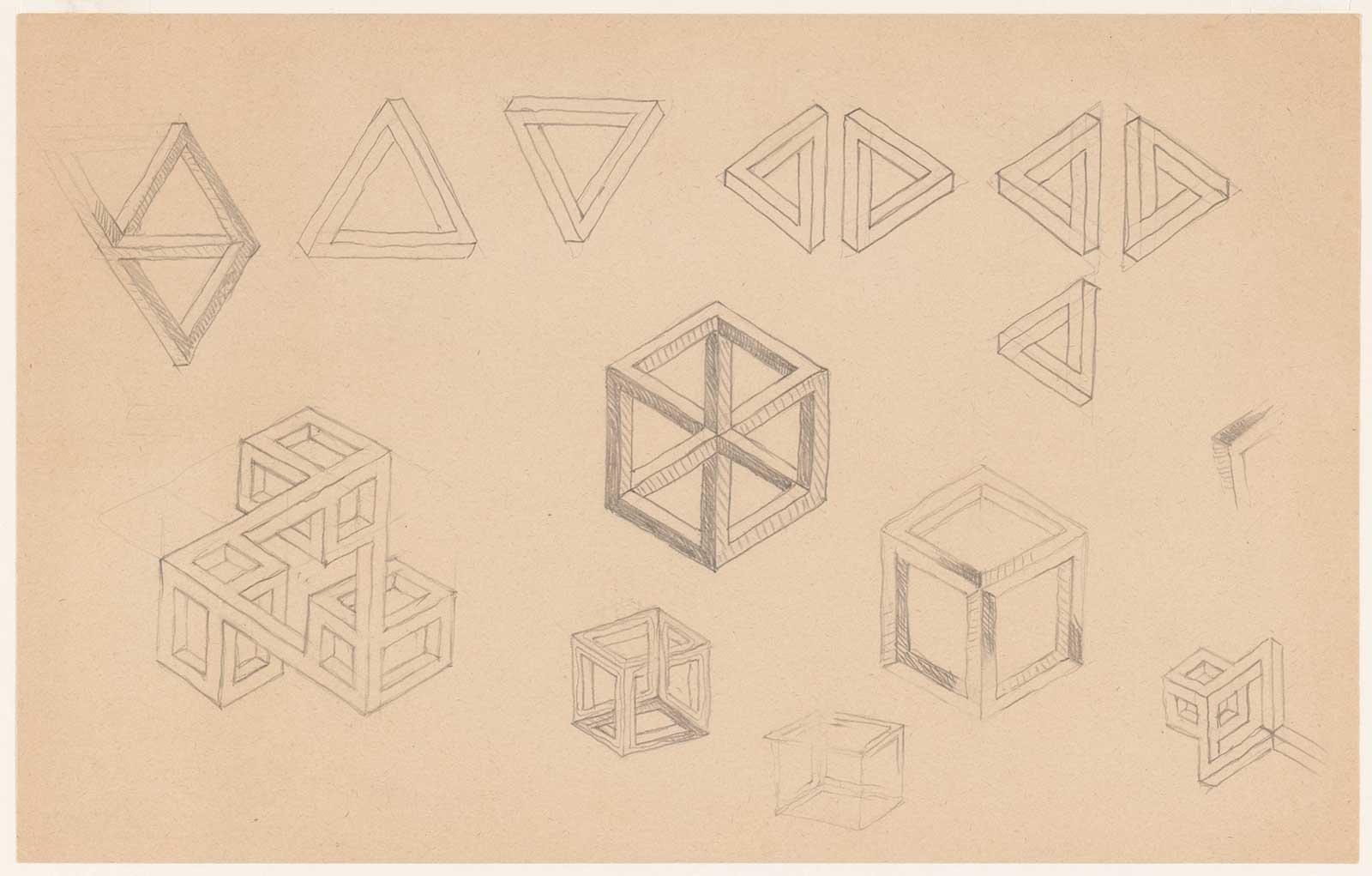

Incidentally, Waterfall’s creation process was no walk in the park. Escher tinkered with the composition a great deal. He came up with the idea for the image through the mathematician Roger Penrose and his father Lionel Penrose. In an article in The British Journal of Psychology (volume 49, February 1958), they showed an ‘impossible triple bar’. A shape that can exist on paper, but not in real life. The three right angles are normal, but they are improperly and impossibly interconnected to form a kind of triangle. The shape was previously devised by the Swedish graphic artist Oscar Reutersvärd (1915-2002), although the Penroses were not aware of that.

They in turn invented the triple bar after Roger Penrose visited Escher’s one-man exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum in 1954, which was held in response to the International Mathematical Congress that year. By using the Penrose triangle as the basis for the watermill in Waterfall, Escher closed the loop. Incidentally, this was something he had already done in 1960 by using the ‘impossible staircase’ by Penrose Sr and Penrose Jr, which was also inspired by the Escher exhibition, for his lithograph Ascending and Descending.

In a letter to the American collector Cornelius van Schaak Roosevelt (1915-1991), grandson to former president Theodore Roosevelt, Escher drew this triple bar. In the letter, dated at 30 November 1961, he wrote:

‘Waterfall, which is brand new, is based on an idea from the two Penroses. It is another of their exciting “impossible objects”, a copy of which is included below. Published in the British Journal of Psychology, February 1958. Title of the article: ‘Impossible objects: a special type of visual illusion’ by L.S. Penrose and R. Penrose. They mention my name in this article too.’*

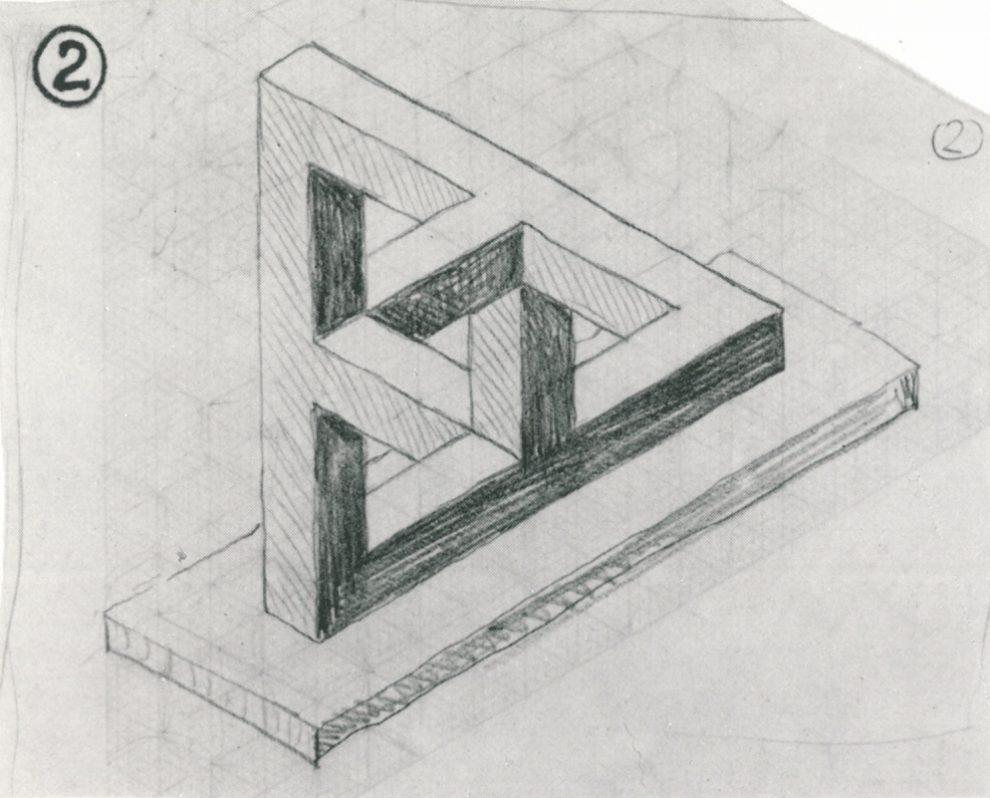

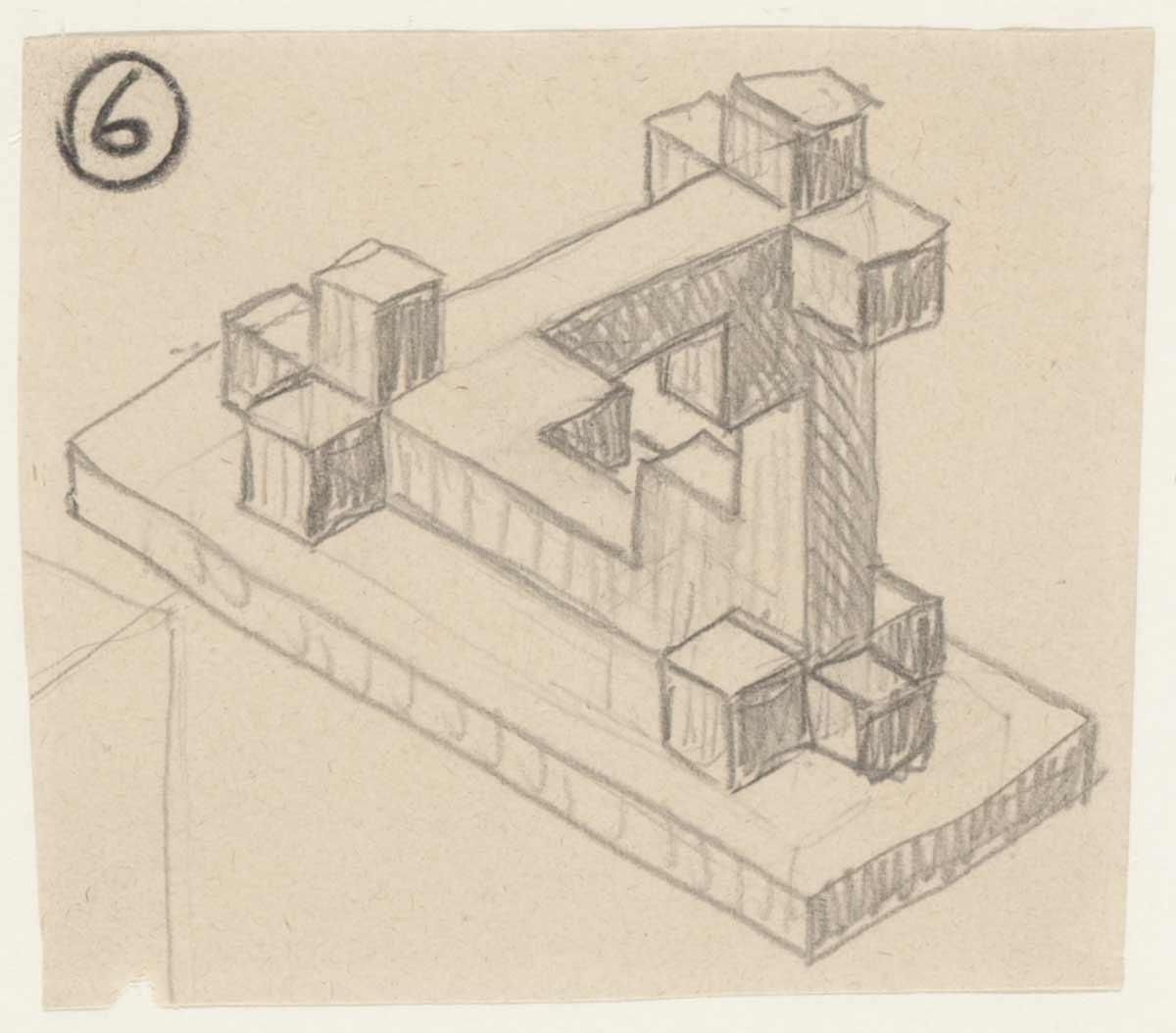

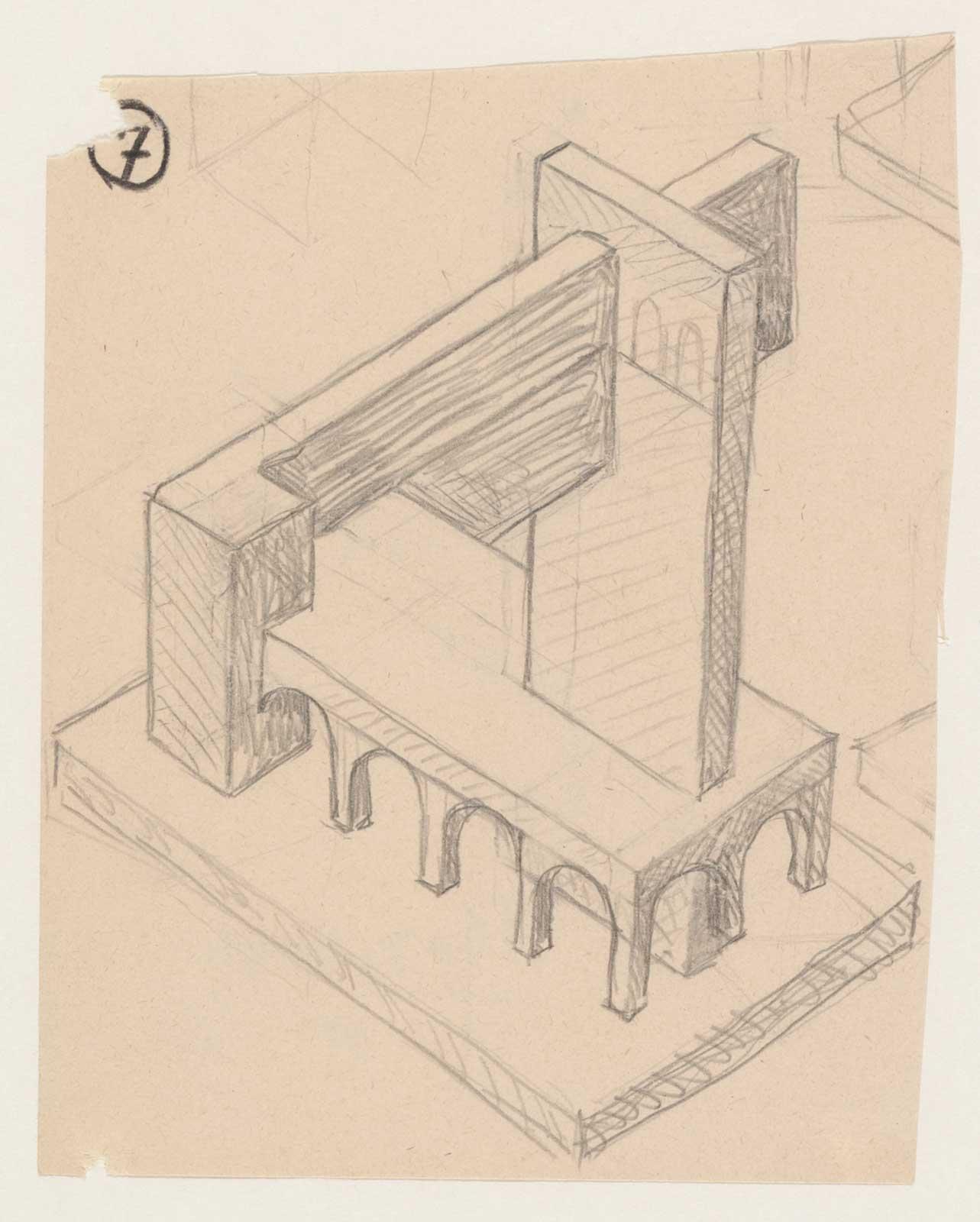

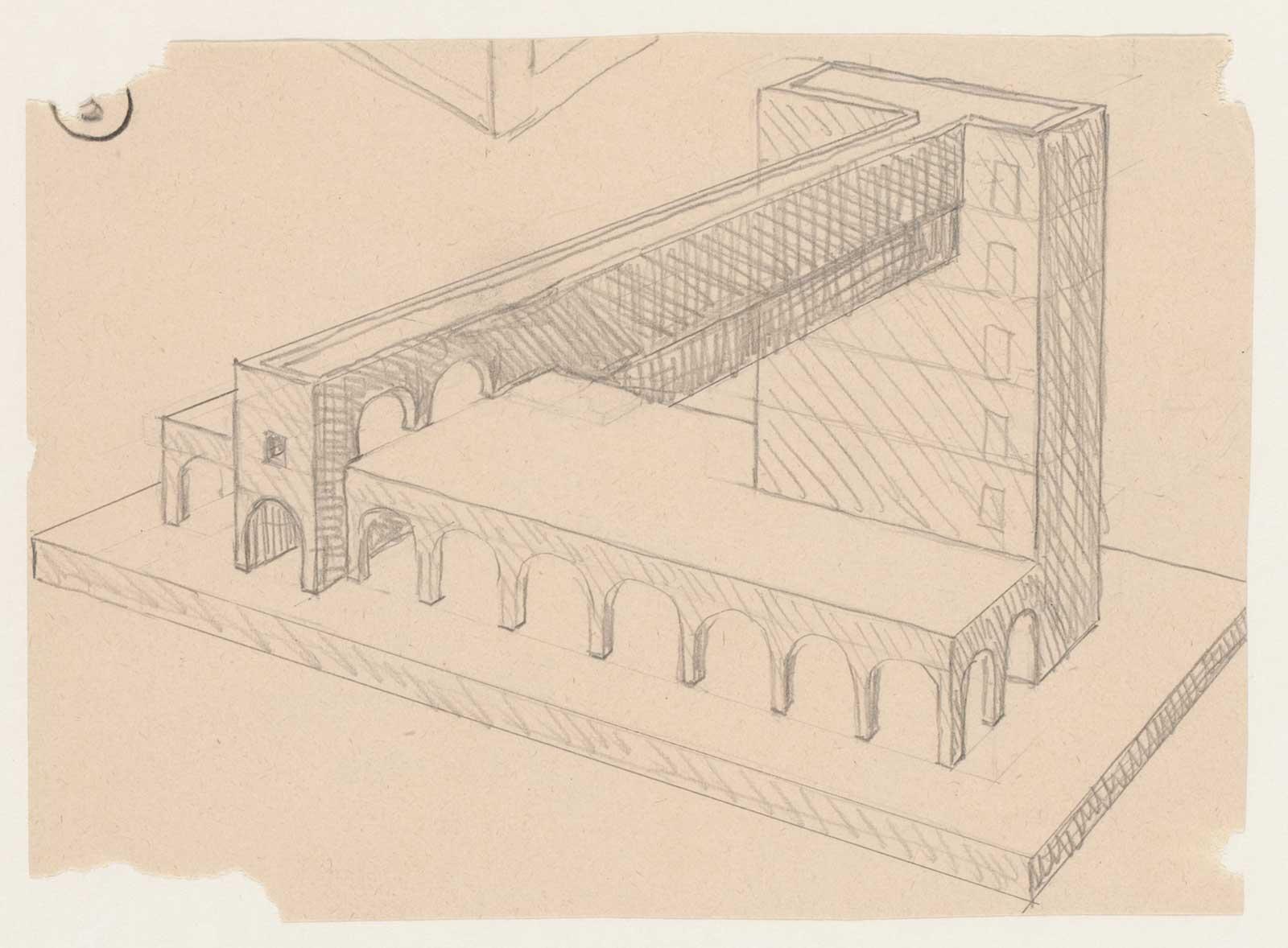

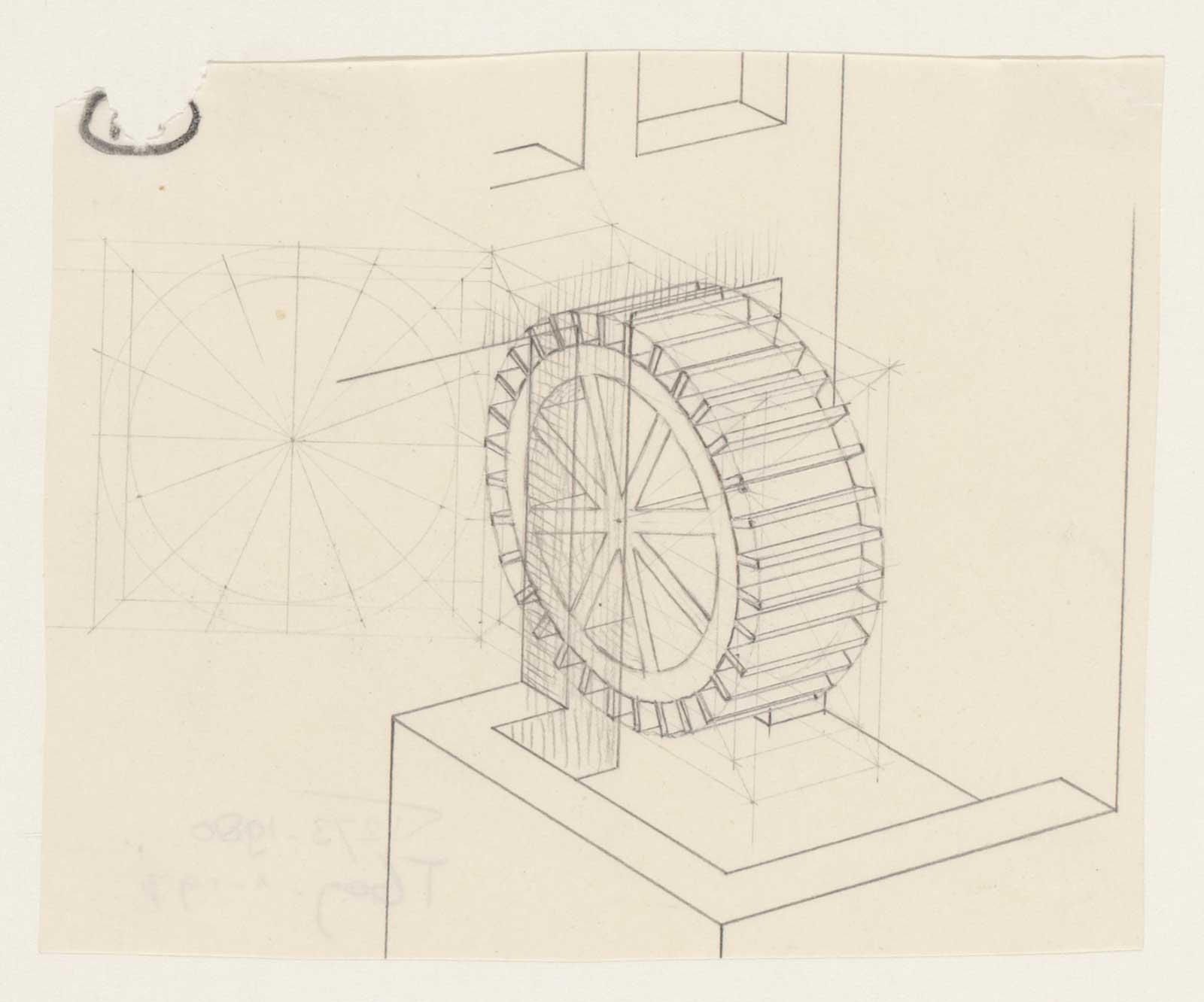

He combined three of these ‘triple bars’ (see drawing 2) and started sketching to make a building out of it. Initially without water. But after some sketches, Escher realised that something was missing, something that could illustrate the absurdity of this building even better. That is when he struck upon the idea of the flowing water. Water always flows to the lowest point, a fundamental principle familiar to everyone. But by having water flow over a structure like this, Escher succeeded in making the deepest and most distant point simultaneously the highest and closest too. The water falls down again and the flow commences afresh. Perpetual motion.

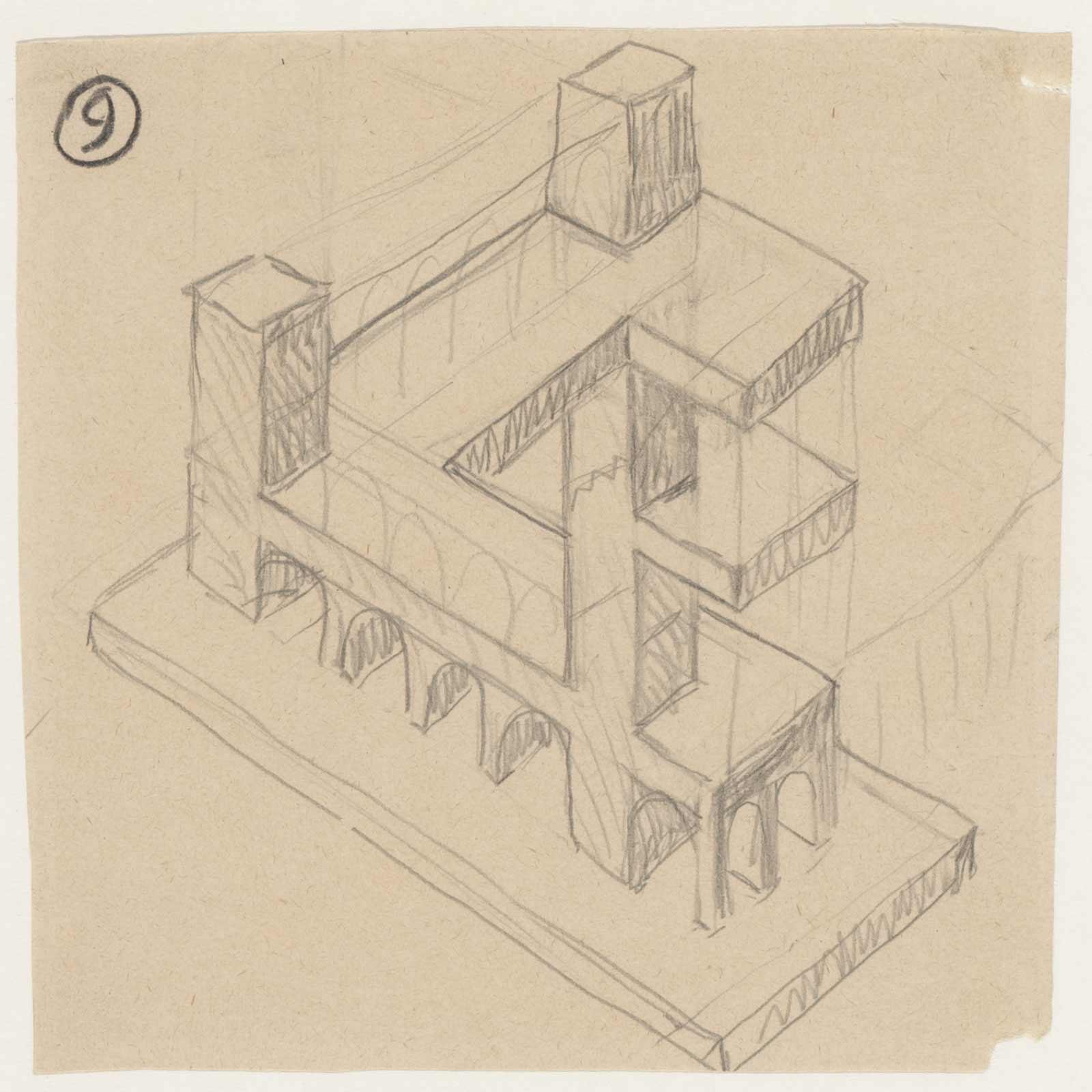

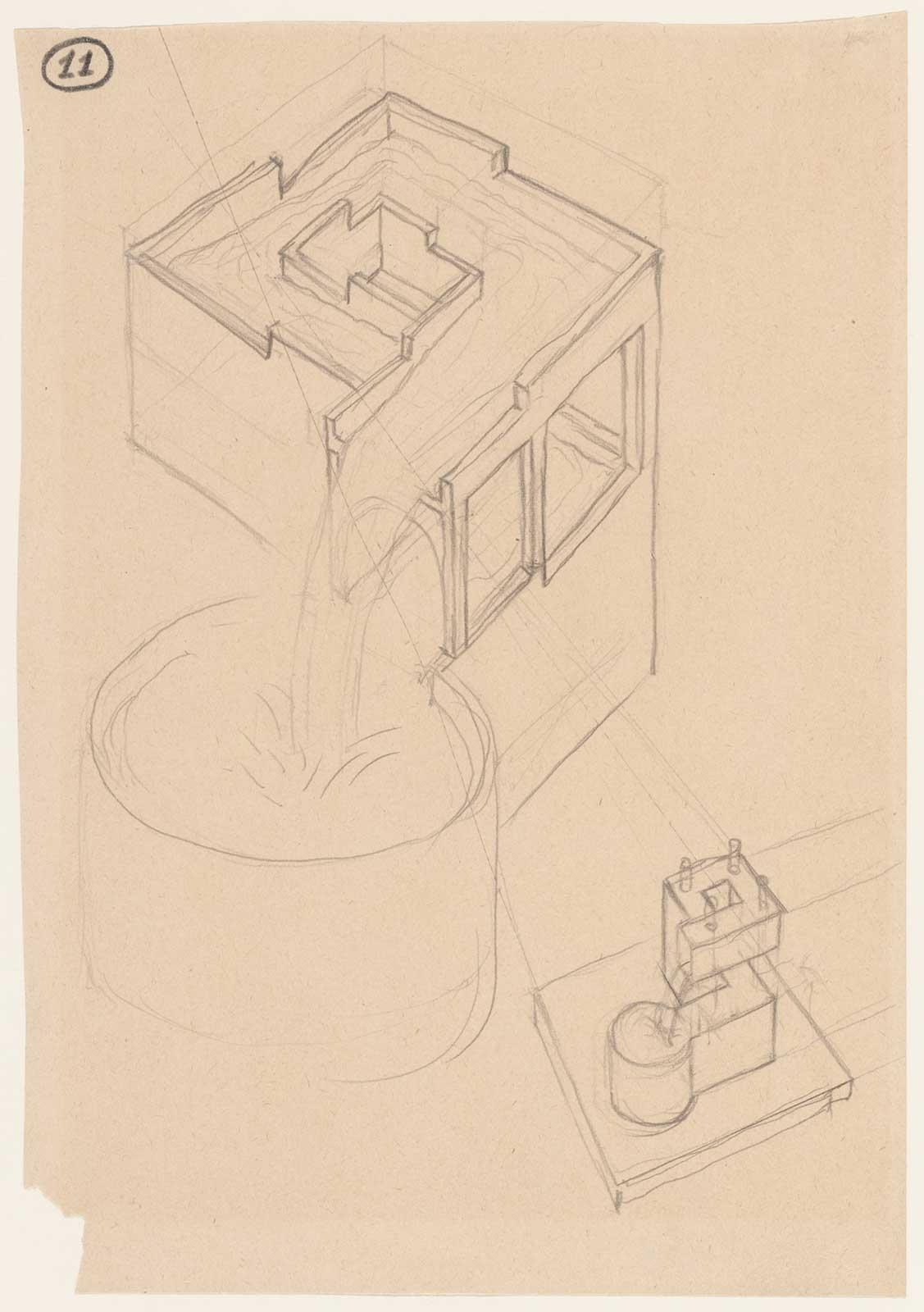

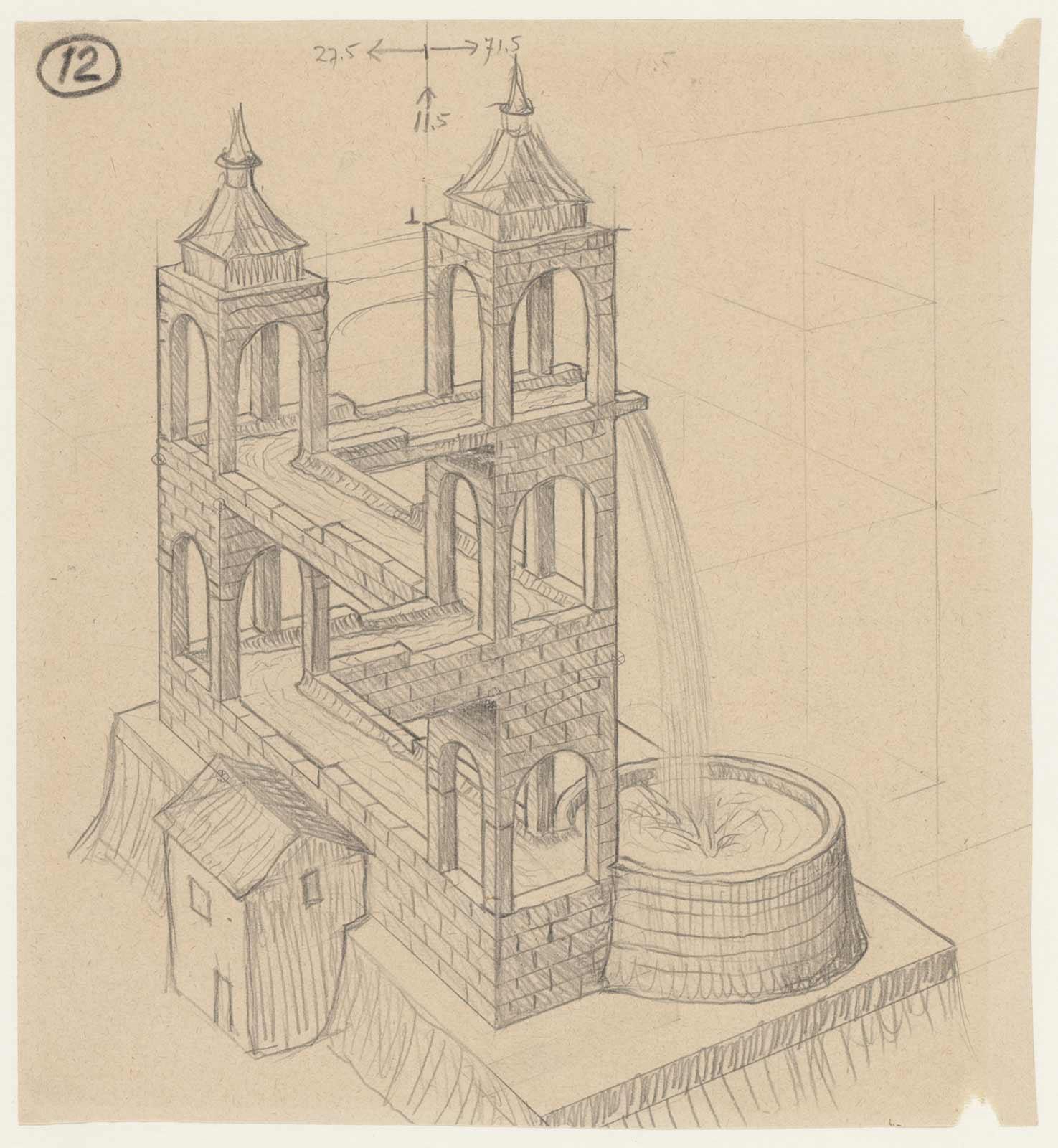

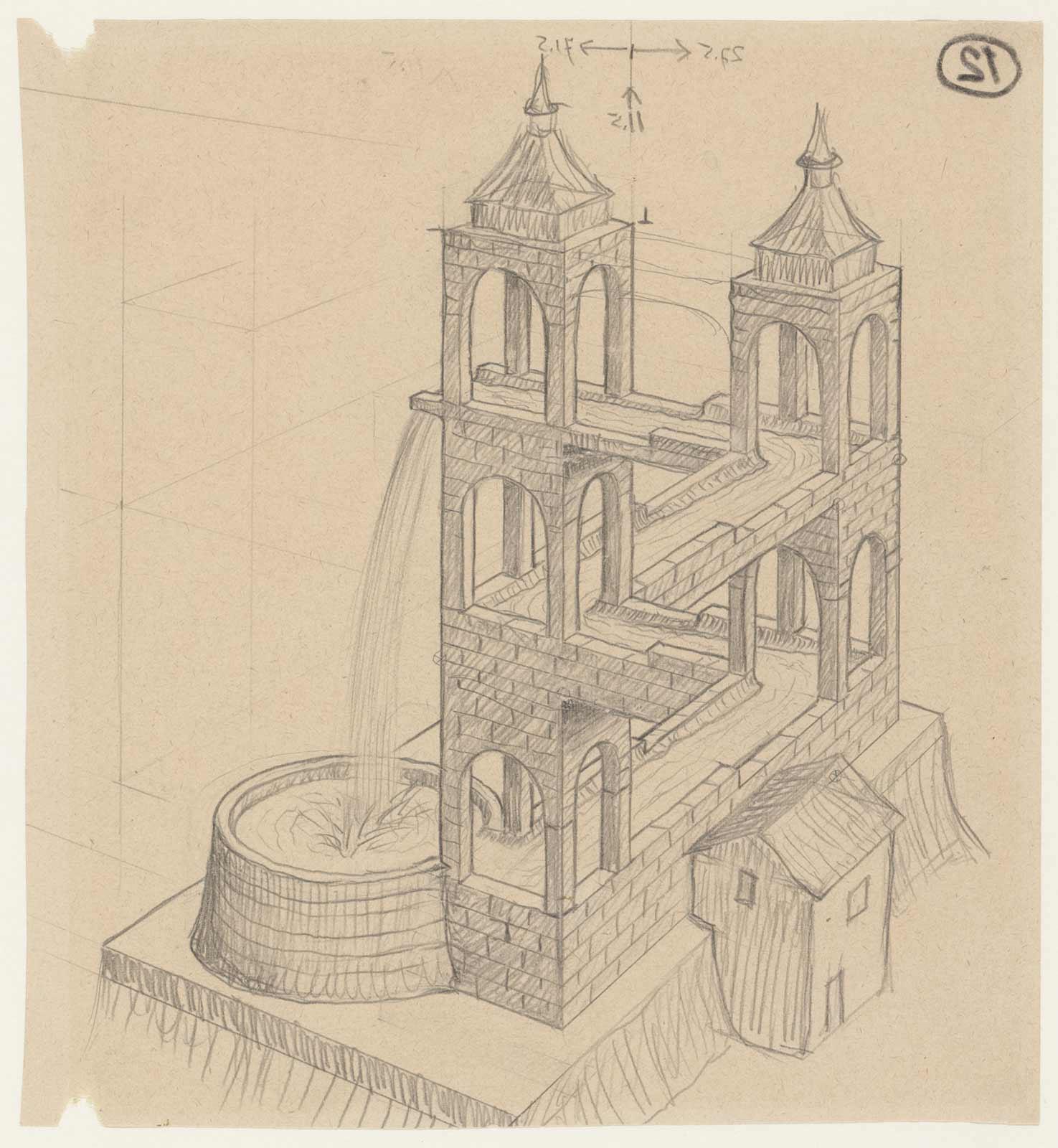

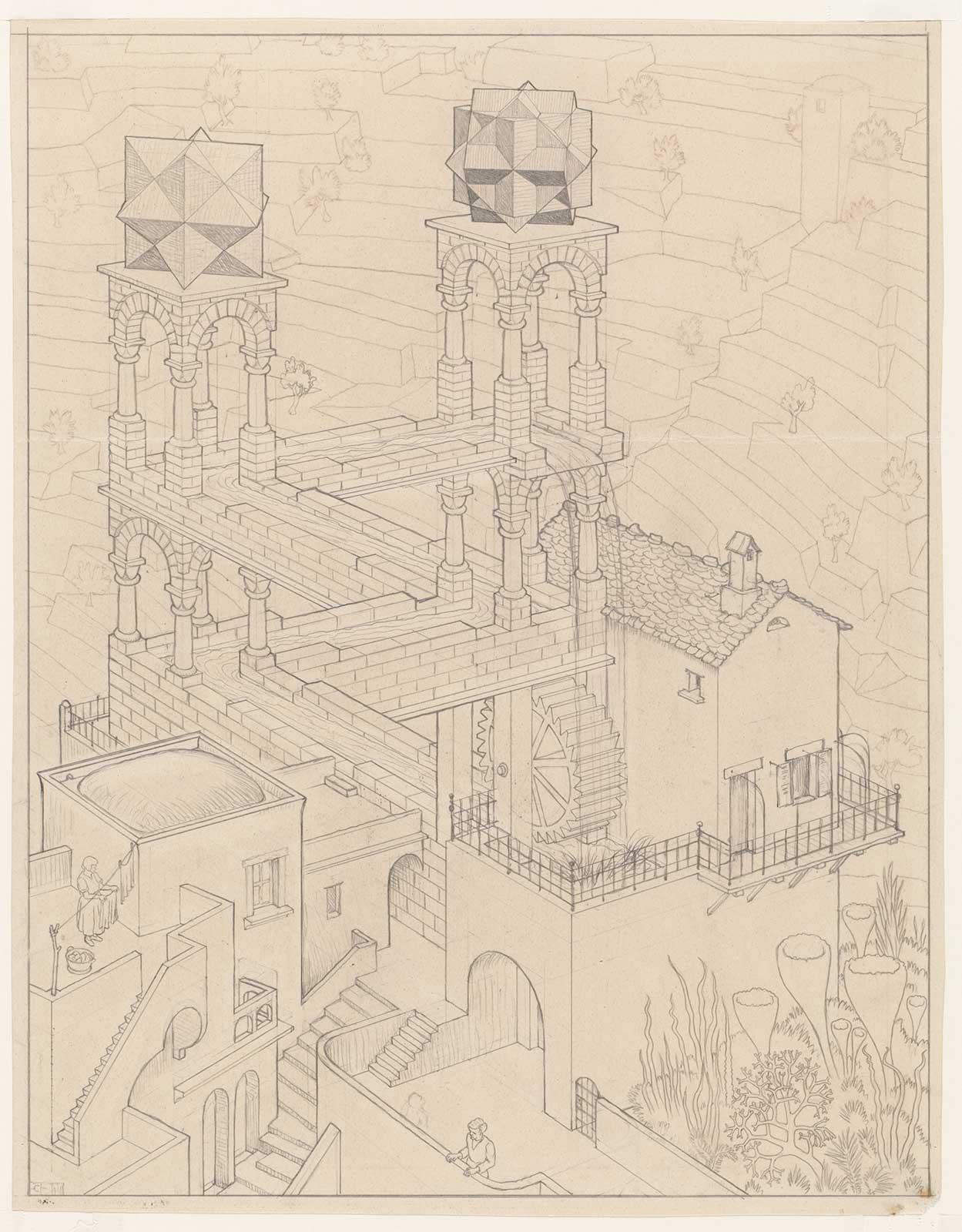

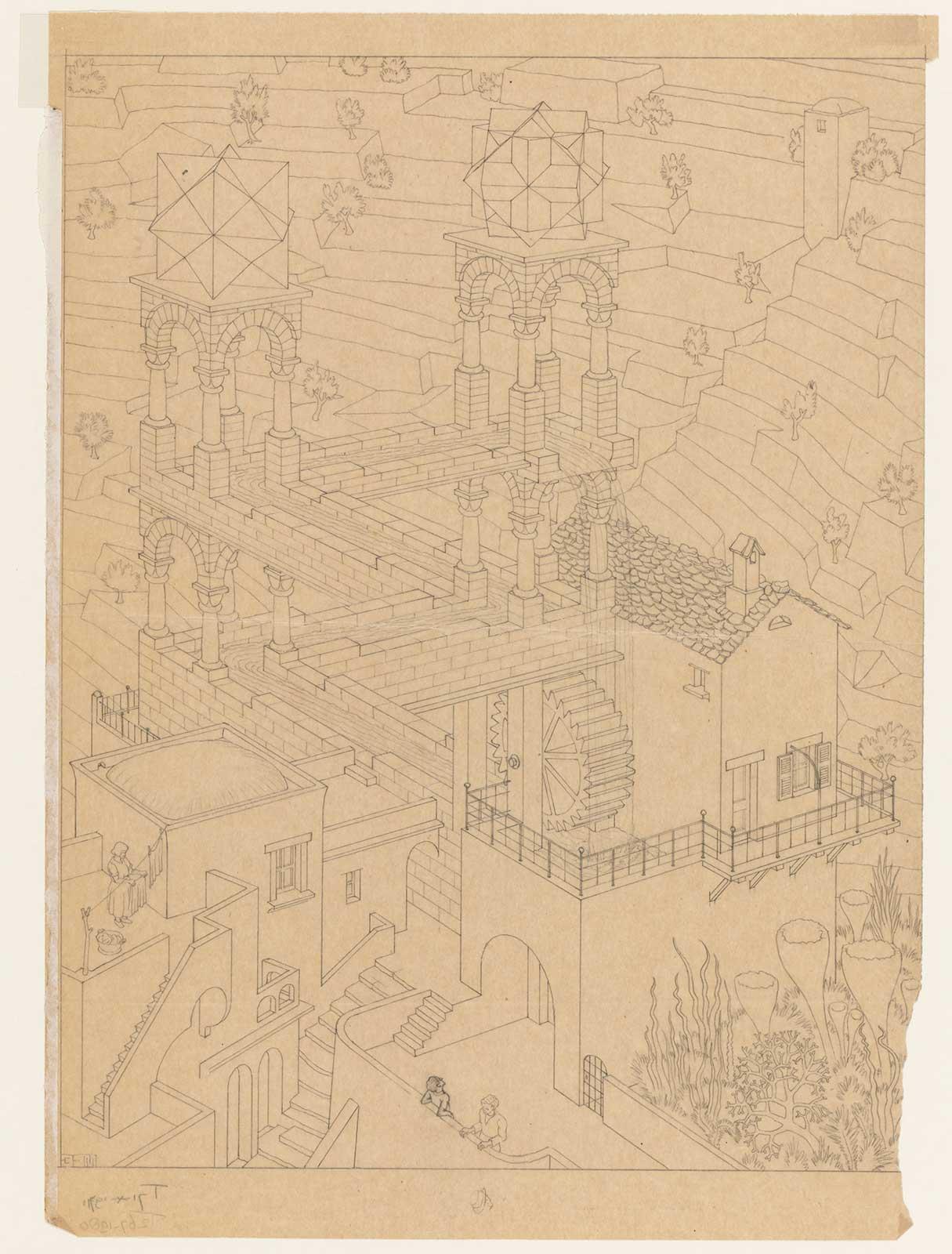

Escher is not content to stop at having water flow through the structure. He continues to develop the shape of the building. The water falls from the top to the bottom, so he adds a basin to catch the water and from which it can continue the cycle. He realises that the building needs floors to have a highest point, but he is still looking for a way in which to include these floors. The solutions in sketches 10 and 11 do not make the grade, but sketch 12 marks progress.

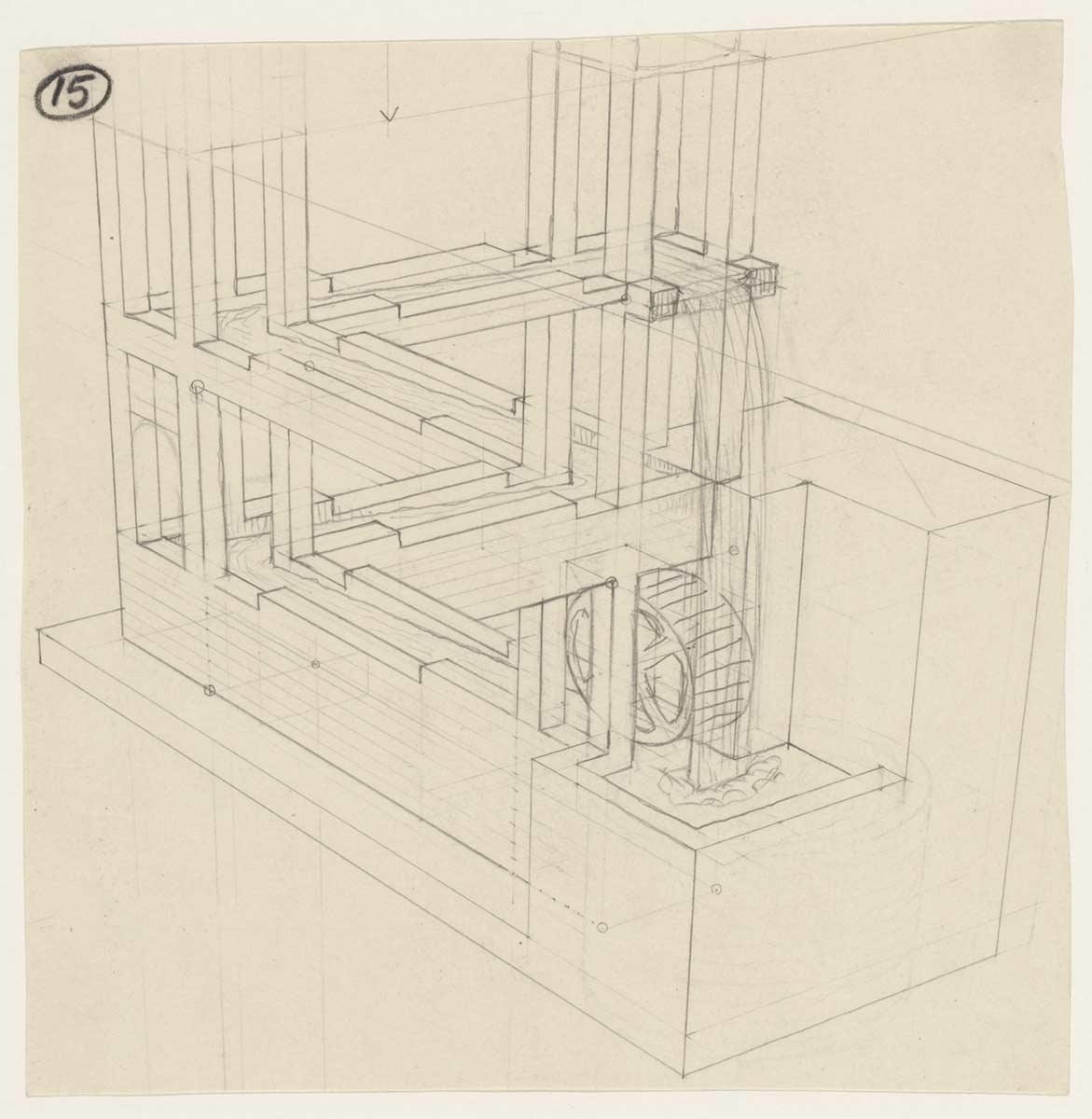

This drawing already contains the brick water channel and the pillar structures that are on every corner of the double truss. He does, however, keep the water basin, and there is another significant difference besides the ornamentation of the structure with surrounding buildings, people and the background: in this sketch, the water falls away from the viewer. In the final version of Waterfall, he has the water go round an extra corner, which makes it fall towards the viewer. Thus reinforcing the perpetuum mobile effect by making the cycle even clearer.

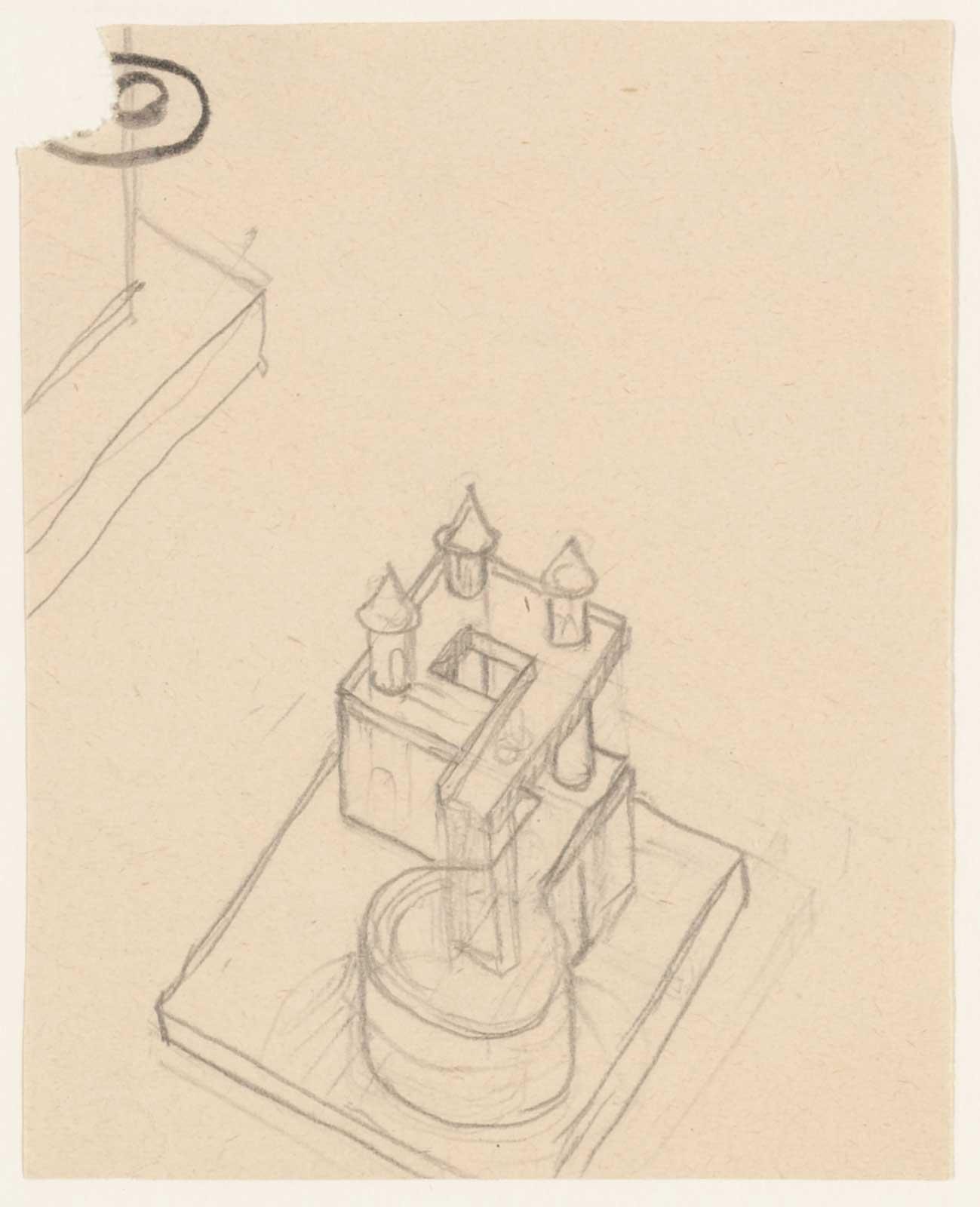

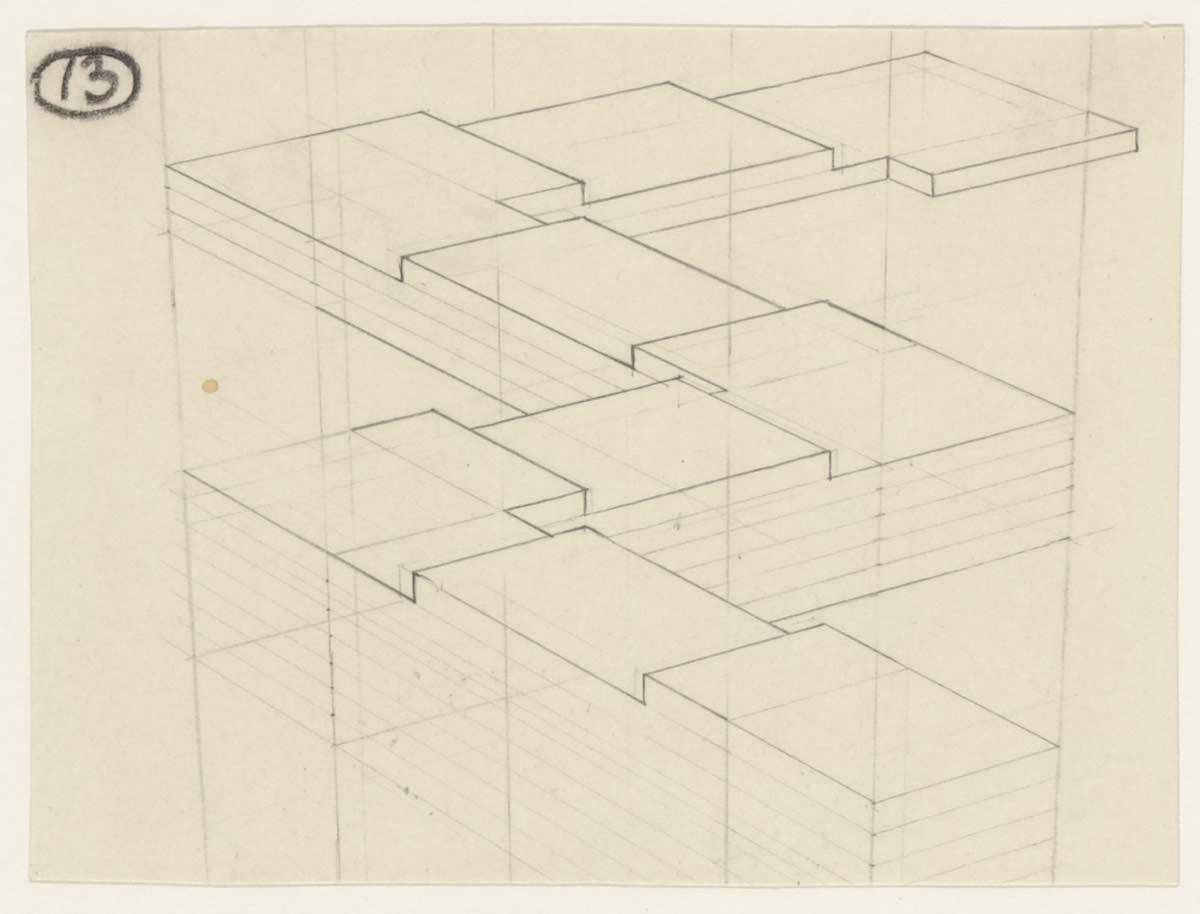

In drawing 13, which is reminiscent of Ascending and Descending due to the staircase structure, he elaborates on what the ‘loop’ looks like, so that the water falls and can start again. Drawing 14 sees him outline for the first time a solution that outperforms the water basin: a water wheel. He continues this in drawing 15, with this drawing actually already containing the final structure as it will feature in the finished lithograph. The precursor stage of that end result is the copy paper that Escher used to put the drawing on the stone.

Yet even at this stage there is a difference to the final print: there are two men in it, in contrast to the print, in which there is only one man looking up at the watermill. Escher stated that this was the miller looking up at his watermill. He only occasionally has to spring into action, adding a couple of buckets of water to compensate for loss of water through evaporation. On the towers Escher places two polyhedrons, albeit without any special significance. In his own words:

‘I put them there simply because I like them so much: to the left three intersecting cubes, to the right three octahedrons’.

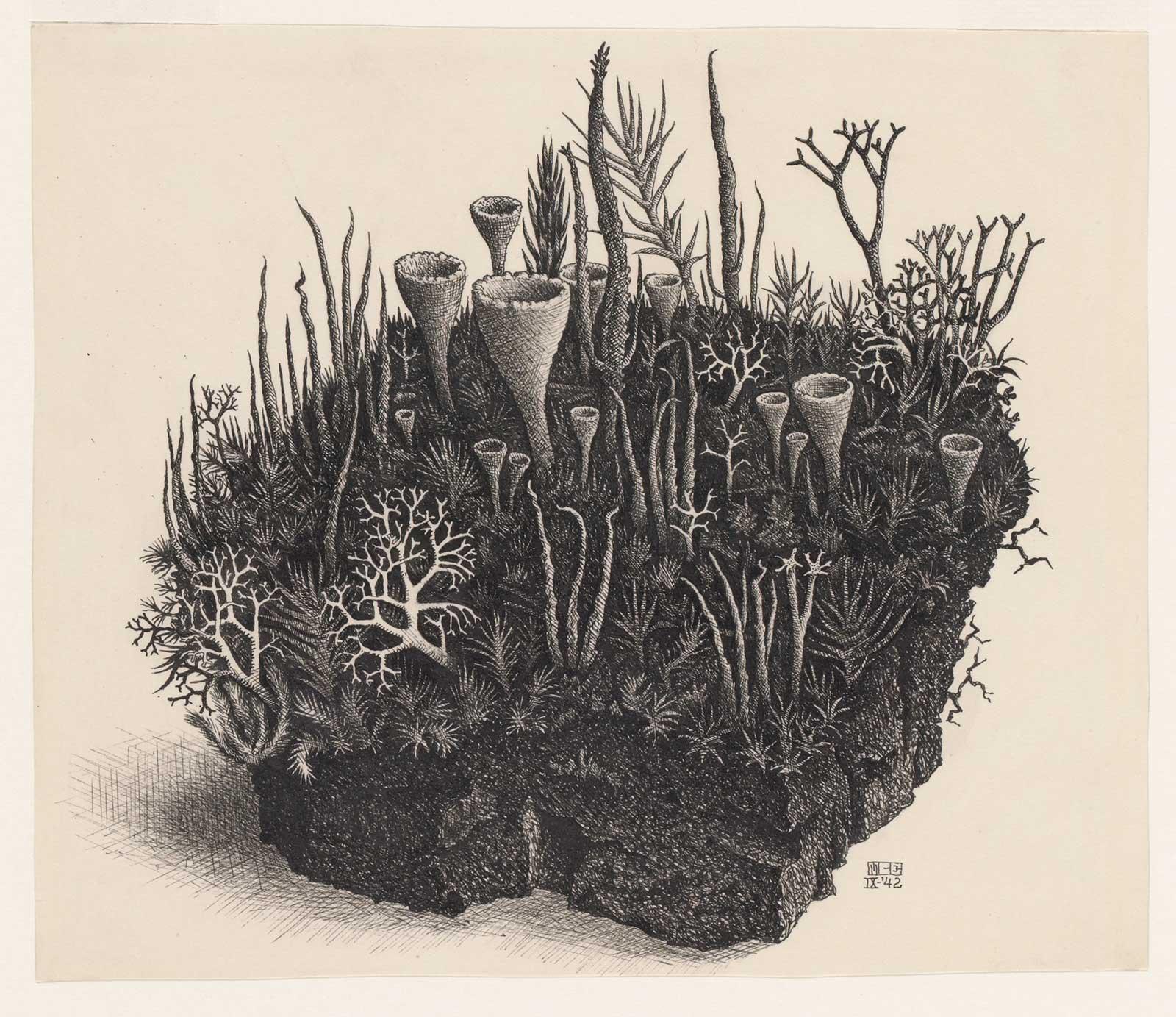

Finally, there is a separate drawing of the striking plants that Escher places next to the buildings. A group of plants that is more reminiscent of a coral reef than of a garden. These are mosses that Escher enlarged significantly. A drawing he produced as far back as 1942 and thus was recycling 19 years later for the purposes of this lithograph. Along with the polyhedrons on the towers, they serve to reinforce the defamiliarising effect. But the presence of realistic buildings surrounding the mill and the Italian terraced landscape in the background temper this effect. By combining possibility and impossibility, realism and fantasy and reality and unreality, Escher creates a print that you will never forget.

A mirrored version of the final drawing and the end result. Compare them by moving the slider.

* Doris Schattschneider, Michele Emmer (editors): M.C. Escher's Legacy - A Centennial Celebration, publishing house Springer, pages 56-57

More Escher today

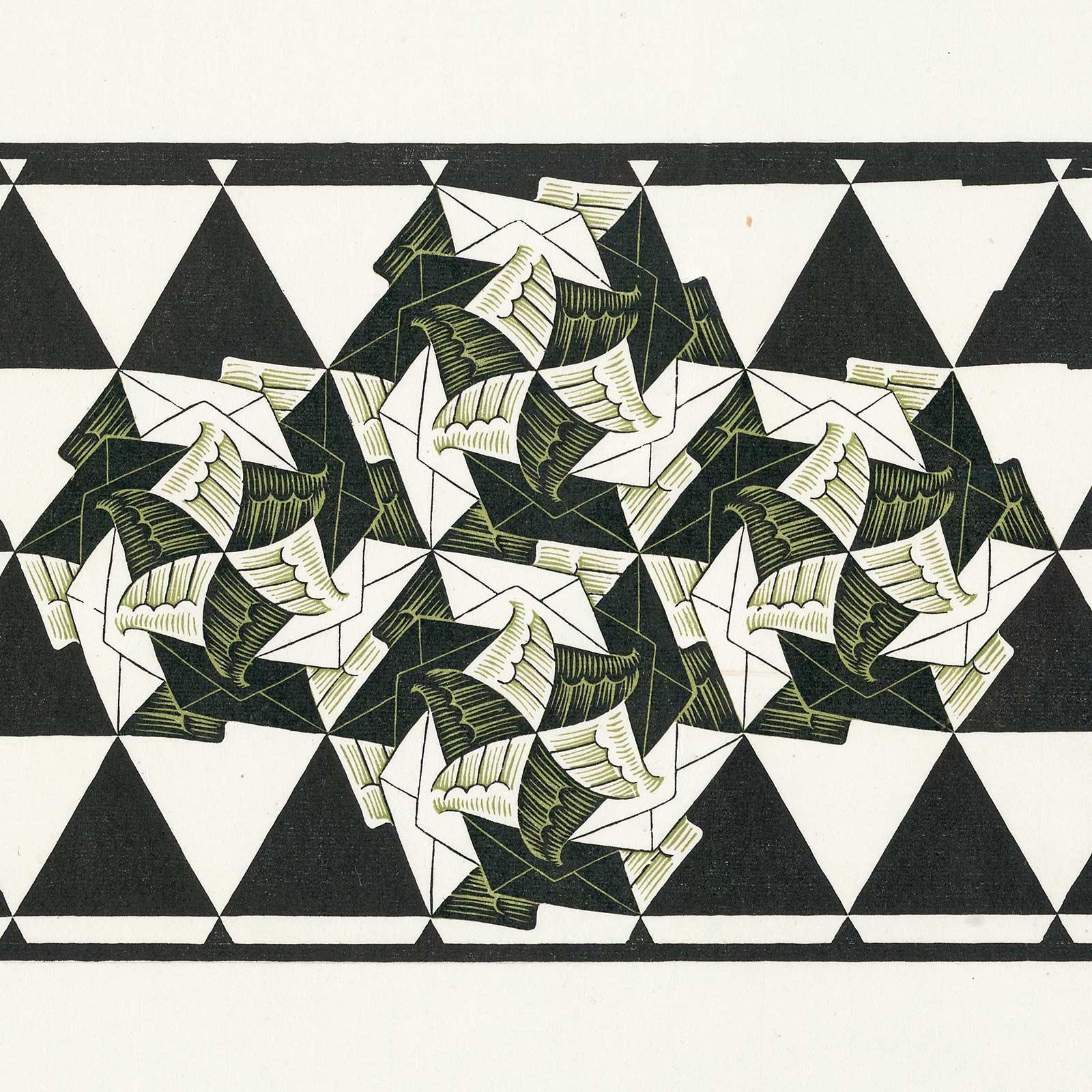

Flying envelopes