On 1 March 1958, Giacomo Balla, one of the most important artists of futurism, died. Escher probably did not know him personally, but he was familiar with his work. There are a number of surprising similarities between the futurist Balla and the early work of the graphic artist Escher. More on that later.

Originally, futurism was an Italian art movement that existed only briefly, from 1909 until the time Italy entered World War I in 1915, but it holds a special place in art history. This is due to the ambition that the futurists exuded and the explicit political component to the movement. Futurism stood for a total renewal of society, where all the old had to make way for the new. Violence was permitted and war was considered a splendid way to expedite the process. The ideas of futurism thus formed the basis of Italian fascism. Futuristic artists embraced the future. Fascism, which arose when futurism was coming to an end, took up that gauntlet.

Italian poet Filippo Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism, which launched the movement on 20 February 1909, already set out these ambitions:

'We shall destroy the museums, the libraries, all forms of academy. We shall glorify war (the world’s only hygiene) as well as militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of those who bring liberty, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and disdain for women.'

More manifestos would follow. On 11 February 1910 Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Gino Severini, Luigi Russolo and Giacomo Balla signed the Manifesto dei pittori futuristi (Manifesto of Futurist Painters). On 2 April of the same year, the technical manifesto (Manifesto tecnico della pittura futurista) followed, which posited that observations do not consist of a still image, but that the environment is in perpetual flux. It contends, therefore, that painting should reflect motion and dynamism. Futurism was thus connected with cubism, the artistic movement that had already tried to capture movement and multiple perspectives simultaneously in one image. Marinetti would consolidate the connection between futurism and fascism in 1919 when he wrote Il manifesto dei fasci italiani di combattimento (Manifesto of the Italian Fasci of Combat), the manifesto of the Italian fascist party led by Benito Mussolini.

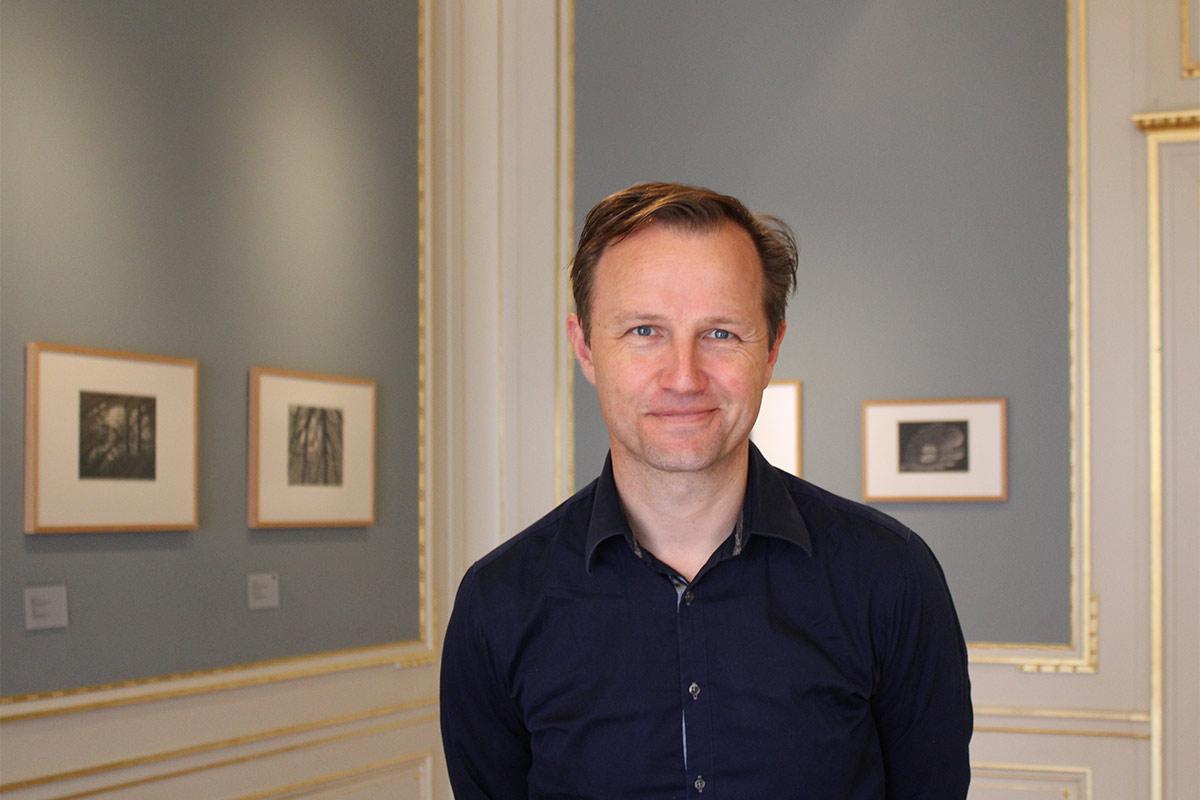

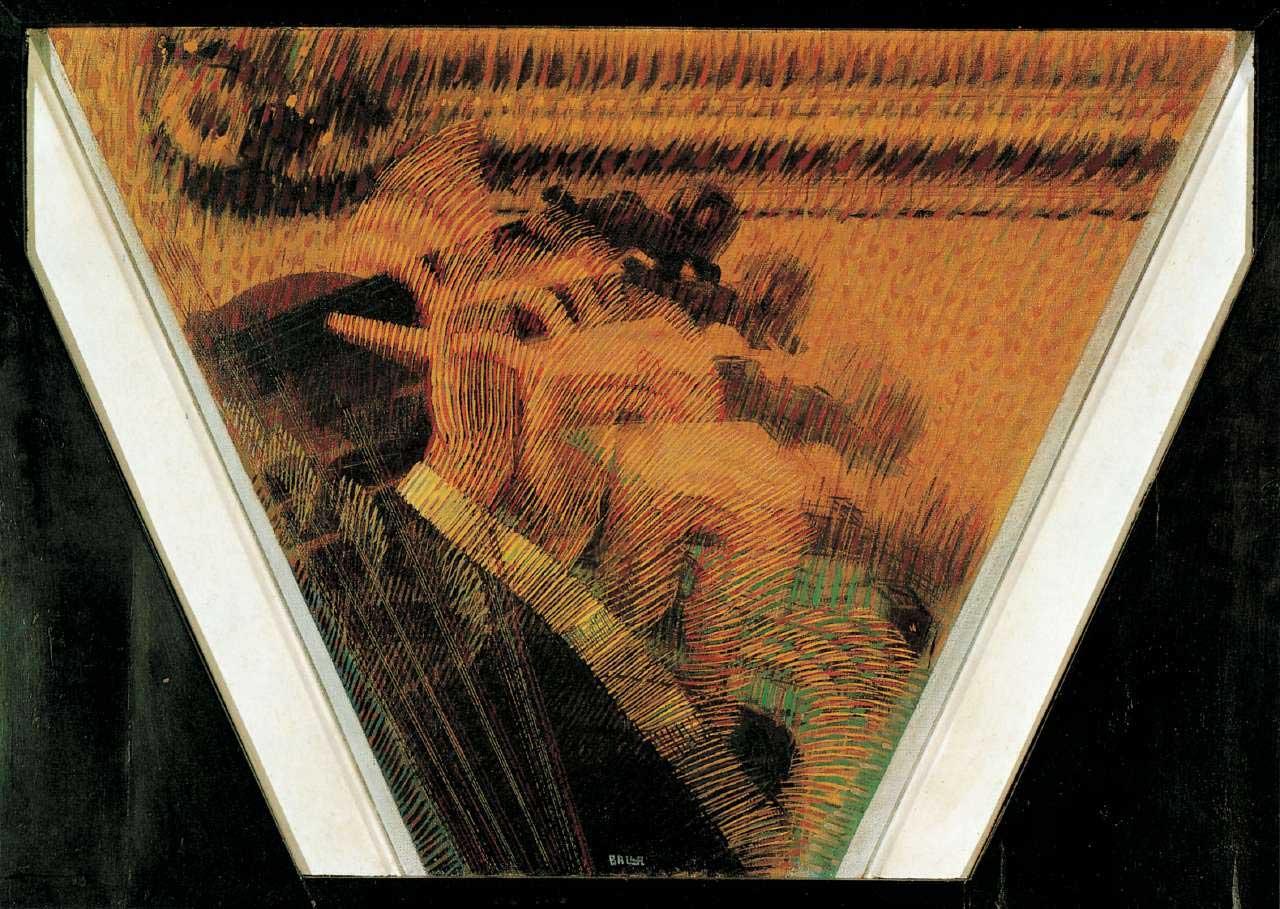

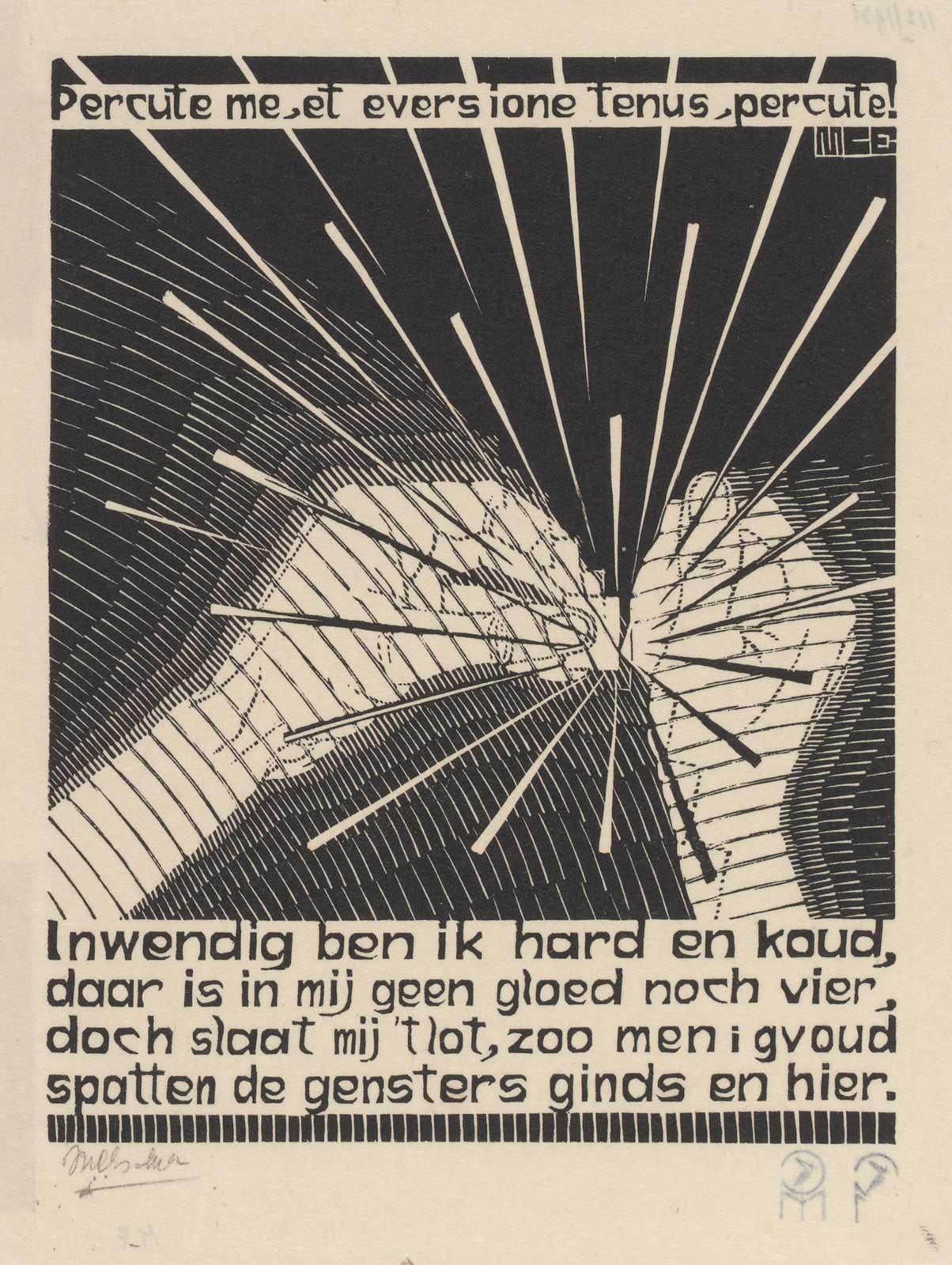

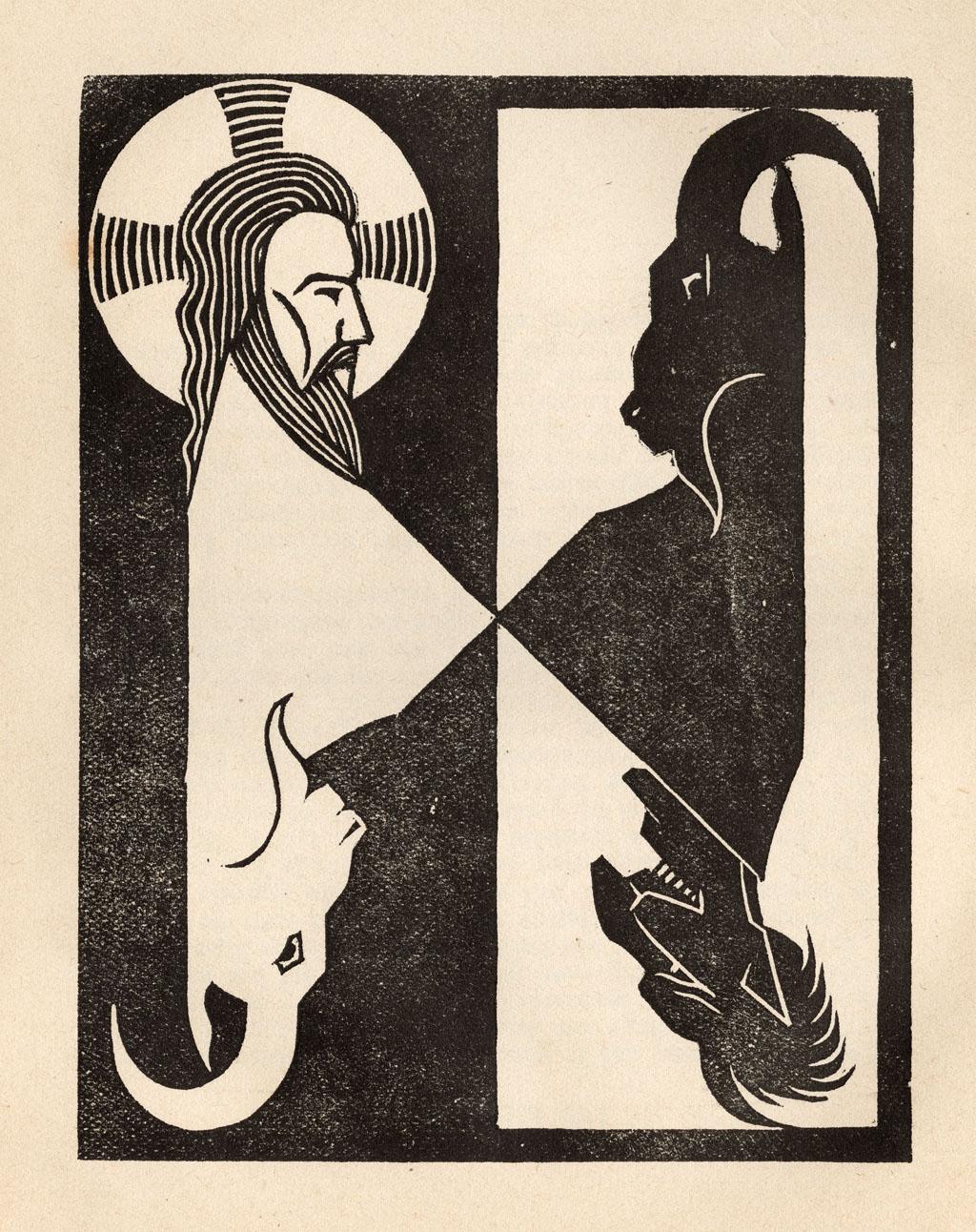

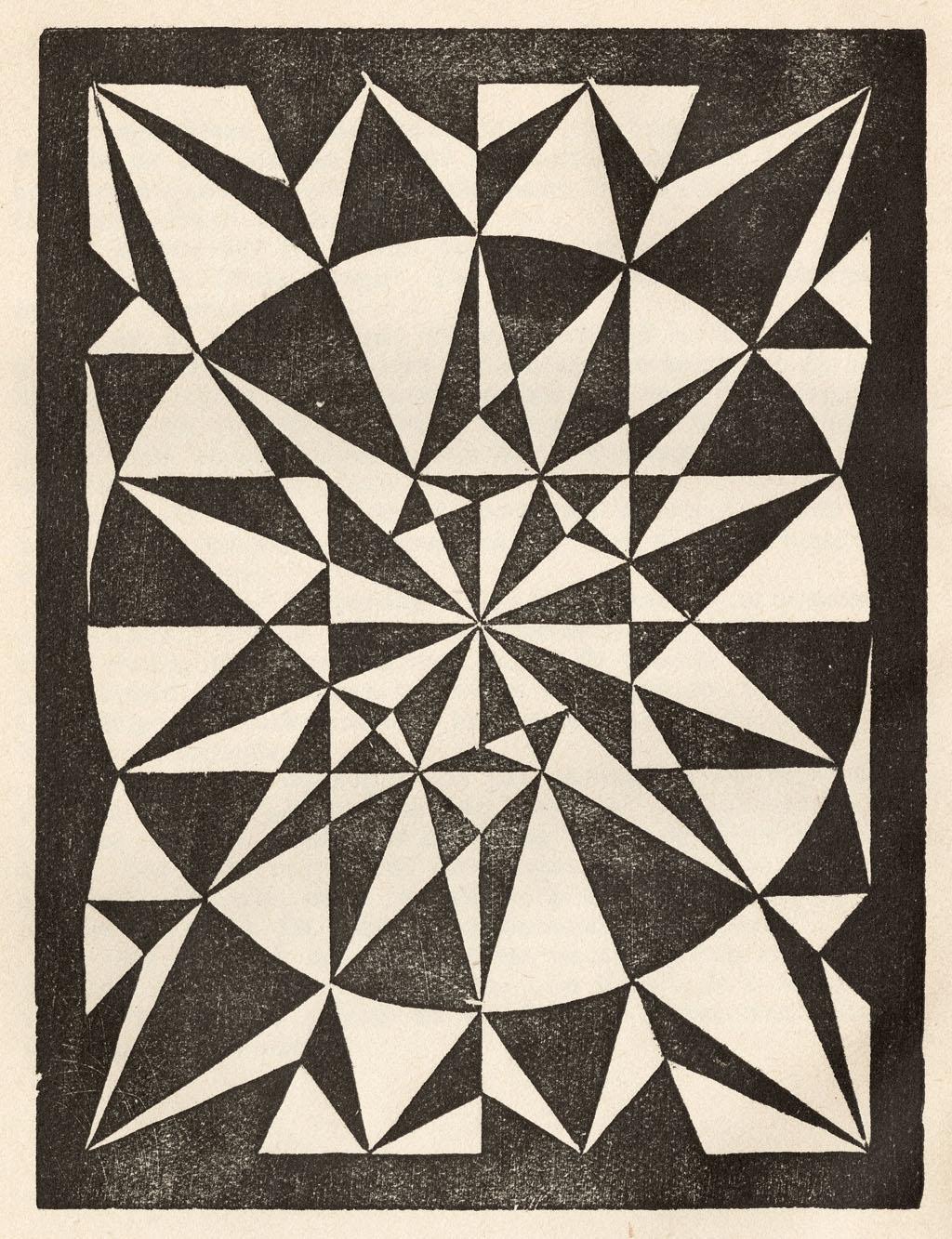

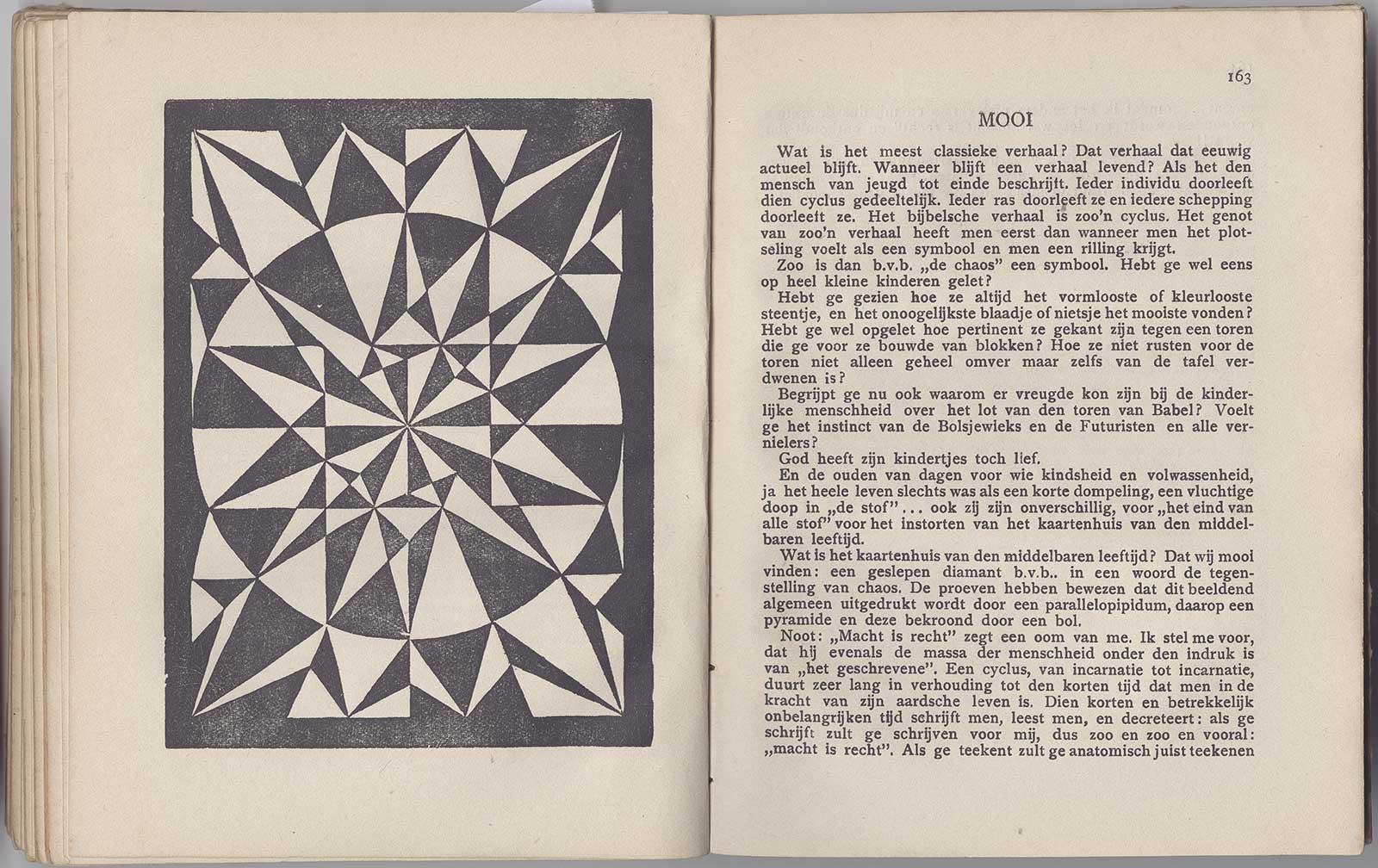

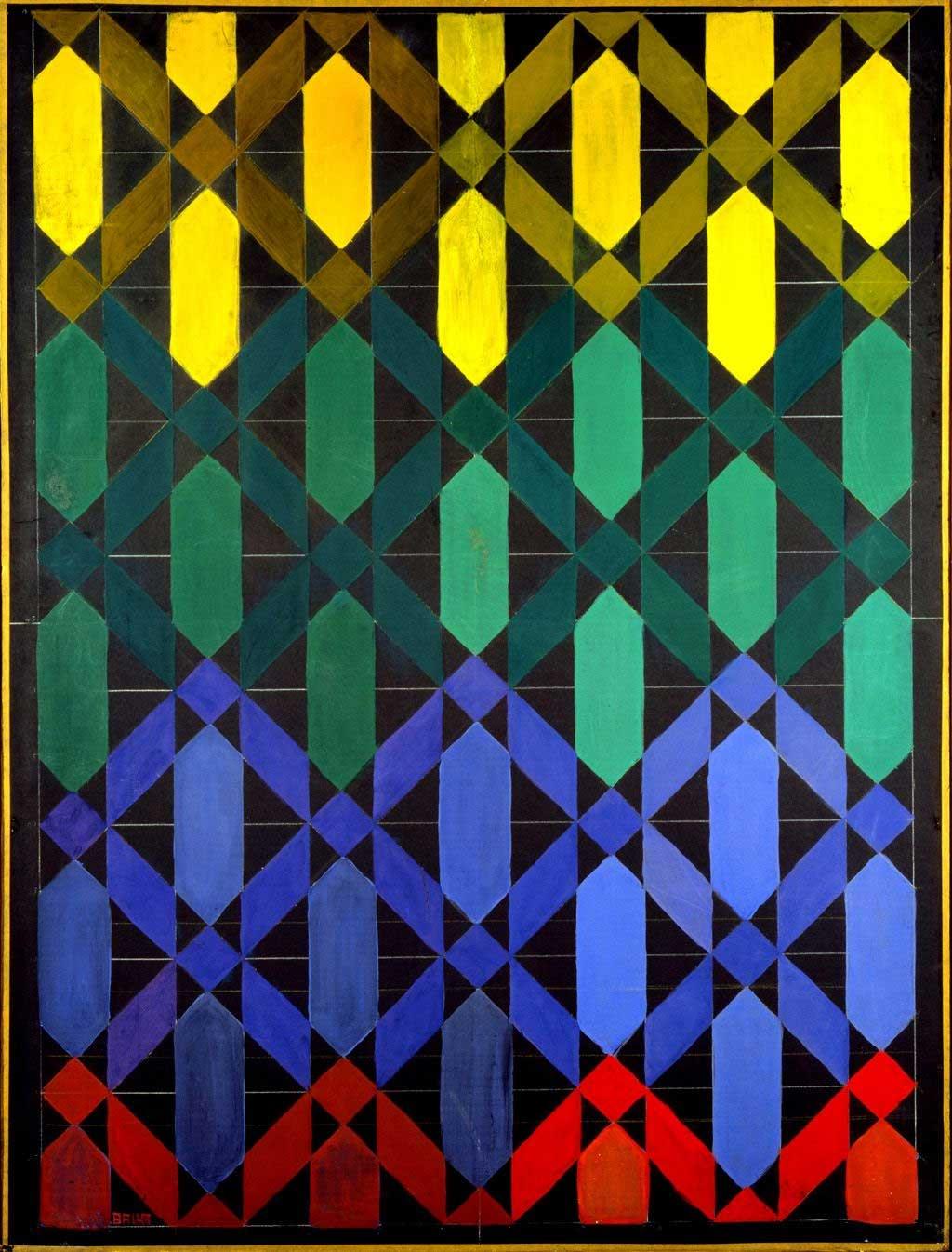

The futurist Giacomo Balla (1871 - 1958) was less outspoken when it came to his political views, but his work would become very popular among fascists. In his work, he focused on light, speed, motion and dynamism and his paintings do exactly what the Manifesto of Futurism prescribed. M.C. Escher was still studying when the movement was active, but he must have been aware of it. Balla’s use of geometric surfaces in the series Compenetrazione iridescente from 1912 has possibly strengthened Escher’s love of geometric figures. Early woodcuts like The Scapegoat and Beautiful from 1921, from the Flor de Pascua series, feature geometric shapes that seem to recall Balla. In Flint, number X from his Emblemata series of 1931, his hands are feverishly busy producing sparks by striking a flint. Speed and motion, recorded on the flat surface. It is reminiscent of Le Mani del Violinista, painted by Giacomo Balla in 1912. Escher likely knew the work of Balla through his friend Giuseppe Haas-Triverio, who exhibited at the exhibitions of the Regional Fascist Trade Unions.

Although there is a positive link between Escher and futurism, the one with the fascists was rather negative. When Escher moved to Rome in 1925, the fascist movement was firmly entrenched. Benito Mussolini was elected Prime Minister of Italy in 1922 and was working to expand his power and strengthen the Italian economy. However, all this was viewed with a certain admiration by the European establishment. After all, Il Duce had ended the social unrest that had prevailed in the country after World War I. Winston Churchill publicly praised him and the Dutch businessman and politician Hendrik Colijn called him a ‘wise man’ in his letters. Furthermore, prominent writers such as Jan Greshoff, J.C. Bloem and Hendrik Marsman were fascinated by the powerhouse Mussolini. The drawings that Jan Toorop produced of him were the first examples of fascist art in the Netherlands

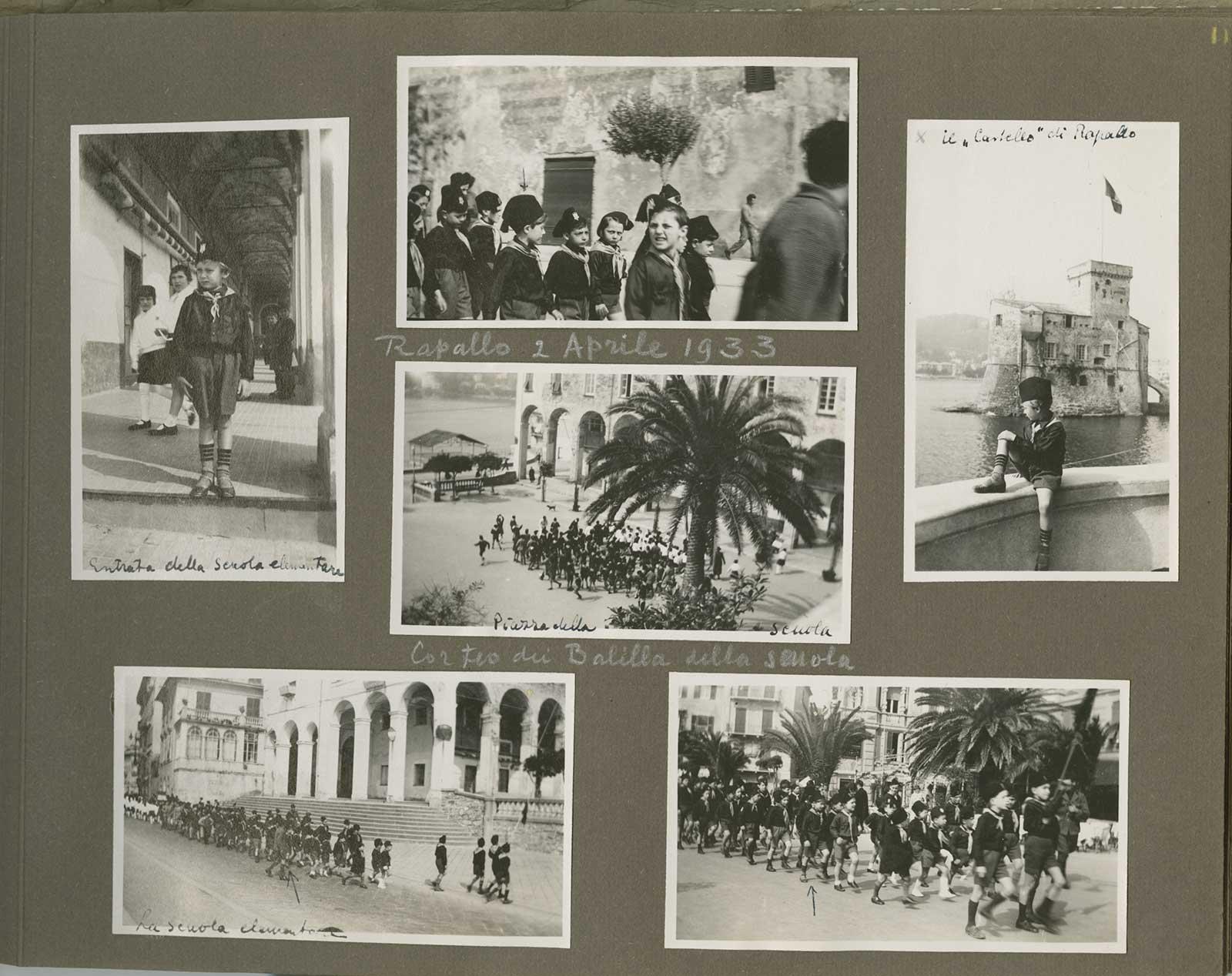

Escher and his family had little trouble with the fascists in the first few years. But that changed as the latter became more vociferous, drawing in more and more young people. This resulted in their sons having to wear fascist uniforms. In the spring of 1933, the family was in Rapallo, east of Genoa. They lived there because Escher had rented their home in Rome to a Dutch couple, the Piersons. Son George was going to school in Rapallo. As a student, he had to march with the members of the Balilla, the youth movement of the Italian fascists. In their black shirts, handkerchiefs knotted around their necks, shorts and with the characteristic headgear (which resembles a fez) they certainly stood out. Maurits and Jetta had great difficulty with this. Eventually, in 1935, they chose to leave Rome for Switzerland. A year before the alliance of the Italian fascists and the German NSDAP.

More Escher today

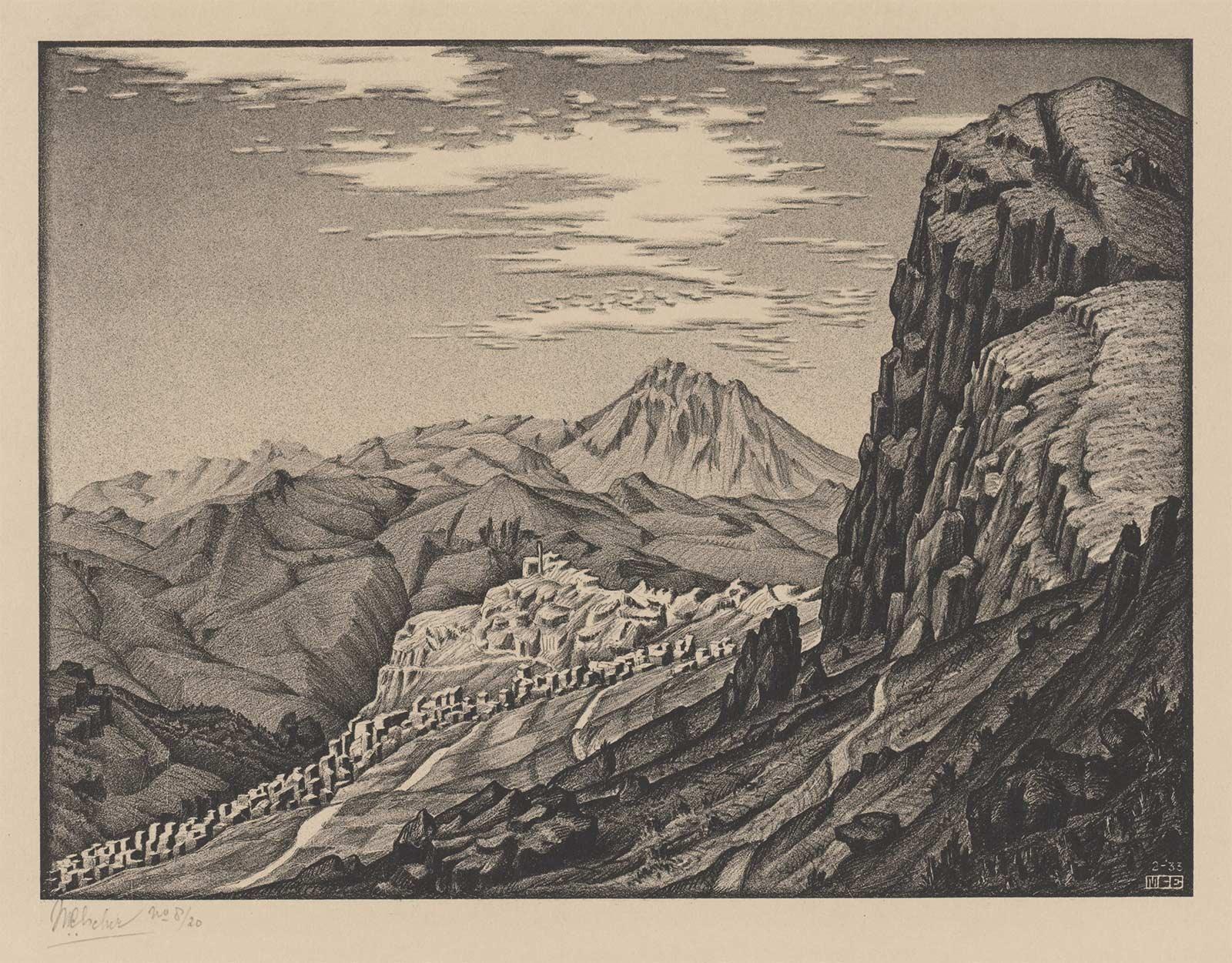

Caltavuturo in the Madonie mountains