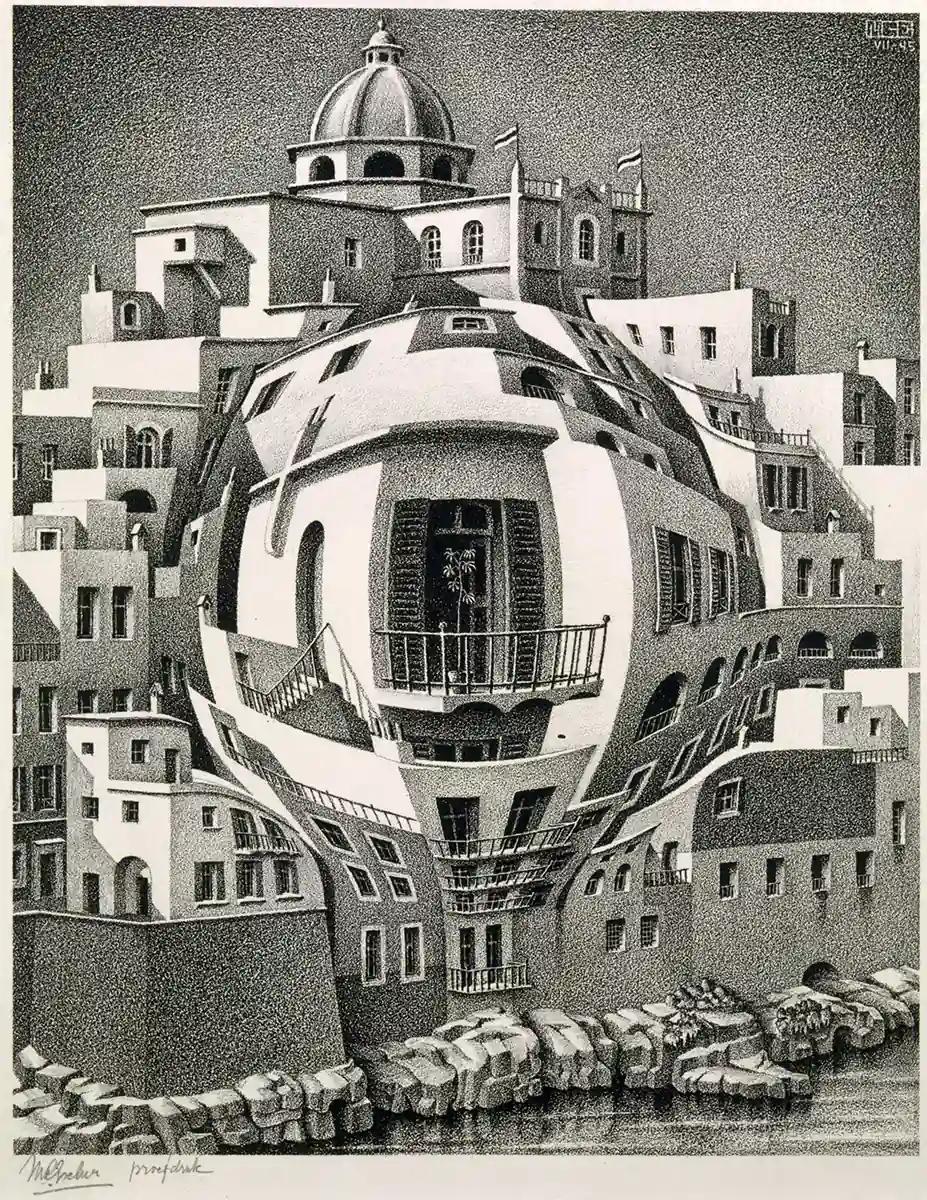

Anamorphosis, related to trompe-l’oeil, is a distorted image that can only be recognised from a specific viewpoint or through a mirror. Such mirrors are often cylindrical, but also sometimes in the form of a cone or pyramid. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 - 1519) was the first to experiment with that, and the technique continued to be perfected in the Renaissance.** Anamorphoses were popular because the maker could hide a message in them that required some effort to see. One high point in this genre is The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein (1497/1498 - 1543), in which a skull can be seen from a certain angle. Escher saw the painting in July 1957, when visiting the National Gallery, and was very impressed by it.***

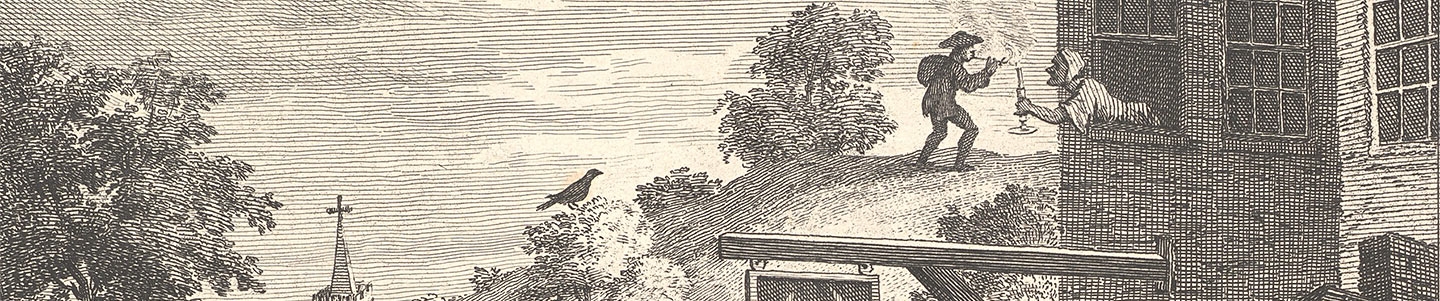

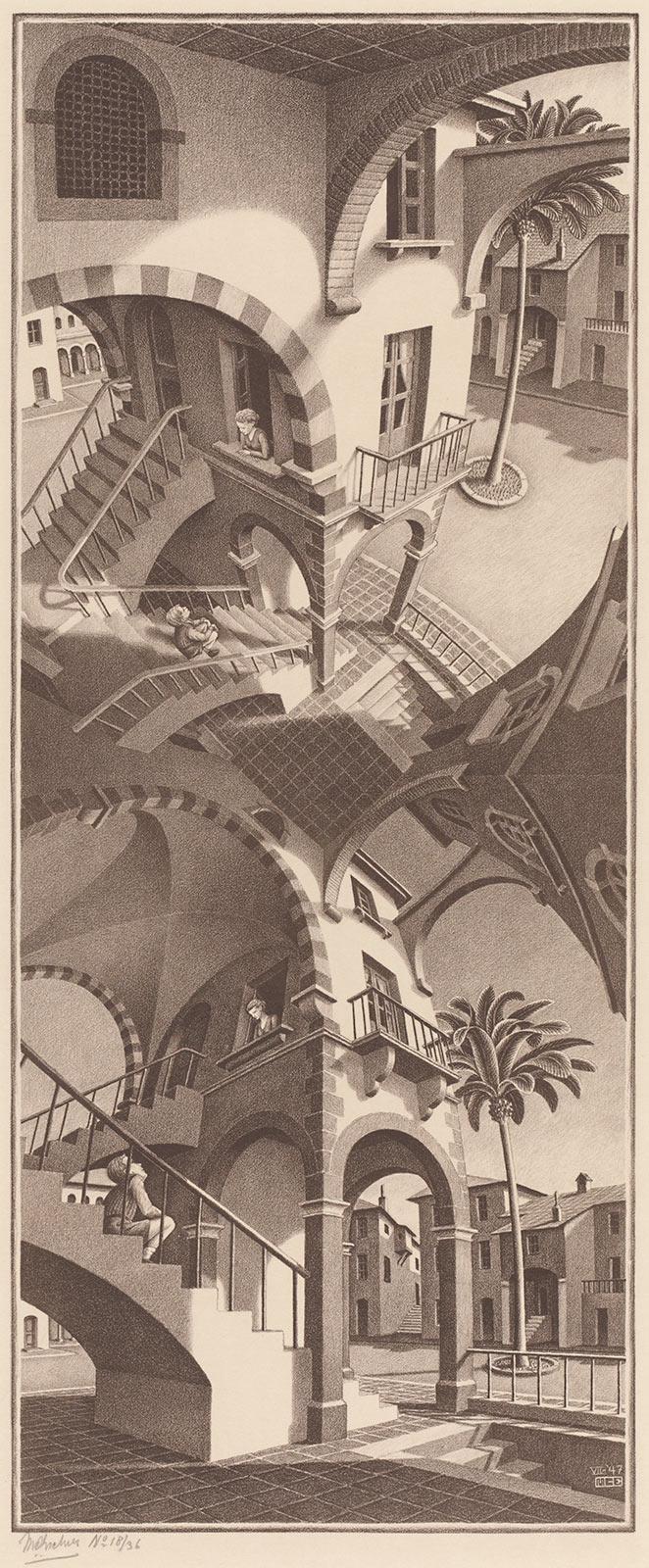

Perspective is an important technique in creating an illusion. It makes many demands of the automated collaboration between brain and eye. The simplest example of this automation is two vertical lines that draw nearer each other towards the top, where there is a horizontal line. This is automatically interpreted as a road, a railway or a waterway going towards the horizon. The first attempts at perspective were made in ancient Greece, but the technique wasn't established until Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 - 1446) carried out a series of experiments around 1425. The first book on this subject was written by Leon Battista Alberti (1404 - 1472) in 1435. In that period, Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea Mantegna (1431 - 1506) succeeded in perfecting perspective.

![<p>William Hogarth, Satire on False Perspective, engraving, 1754. Collection Metropolitan Museum New York<br>The text below the image:<br>Whoever makes a DESIGN without the Knowledge of PERSPECTIVE will be liable to such Absurdities as are shewn in this Frontiſpiece [frontispiece].</p>](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fprdzoomst01.blob.core.windows.net%2Fescher-production-silverstripe-assets-public%2FUploads%2FImageBlock%2Fwilliam-hogarth-satire-on-false-perspective.jpg&w=3840&q=75)